My transformative first trip to Japan · Part 2

13 min read Dec 24, 2021

This photo essay is part two of a four-part series about my transformative first trip to Japan. I spent the first chapter with friends. The second, I spent by myself in Tokyo after most of them had left.

At the beginning of the trip, my friends, being more experienced in traveling around Japan, converted me from an amateur to a savvy tourist. Hence, I felt comfortable setting off by myself. To be fair, Japan is one of the best countries to travel through alone. It’s safe. It’s efficient. Even though many people don’t speak English, most signage appears in at minimum English and Japanese.

While with my friends, my awareness was steeped in conversations and the shared experience of our surroundings. All alone, I turned to observe the world more acutely.

I was already noticing some things. For example, I took a photo of everything single thing I consumed from the moment I took off in San Francisco to the moment I returned more than a month later.

While walking the streets alone, I looked down and saw kaleidoscopic, manga-like manhole covers. I recognized colorful phone booths everywhere even though Japan has extremely high cellphone penetration.

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/60 · ISO

5000

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/60 · ISO

5000

These little details started to loosen me up. They made me feel truly curious and present in a way I didn’t remember feeling since I became an adult.

Art

That sense of curiosity and simply being so far away from home snapped me out of my usual frame of mind. At the time, even though I was a software engineer, a little voice in my head was saying I should pursue design as more than just a hobby.

So leading up to the trip, I would attend design events in San Francisco. When I finally arrived at an event, a tsunami of imposter syndrome would wash over me. A different, much stronger voice of self-doubt would tell me that I wasn’t like the rest of the attendees, that I should go back to engineering where I belong.

But there in Tokyo by myself, I realized the true vastness of the world. The unique blend of efficiency, beauty, history, and motion of Japanese life showed me how different design could be. It gave me the belief that I could find my way into an industry that I admired from the outside for so long.

With a new sense of confidence, I decided to strike out to find some inspiration.

If you’ve been following my writing and photo essays for some time, you know that I love art, especially art museums. They give me a perfect chance to take photographs, enjoy other creative people’s work, and admire buildings that house it all. I even wrote a guide to some of my favorite museums in Japan some time ago.

One evening, I set out from my home base in Shibuya to explore Cat Street. During the warmer months, it’s home to a vibrant youth culture and street fashion scene. That day, however, the streets were mostly bare, the only sound coming from passing cars and the occasional muffled chatter.

I was there mainly to catch a glimpse of Naoto Fukasawa’s ±0 boutique. I jumped to near the top of my to-do list when Andrew Kim posted some photos of it on Minimally Minimal. Unfortunately for me, the space had found a new tenant, a purveyor of inexpensive trendy watches.

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/60 · ISO

125

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/60 · ISO

125

Disappointed, I continued walking up the street. Then to my surprise, an angular building emerged from my left side, Bank Gallery by Pritzker Prize-winner Tadao Ando. While as small as most of the surrounding buildings, it has the presence of a stealth plane or an oversized work of origami.

The interior, clad in raw materials like concrete and corrugated steel., housed a small gallery with rotating exhibitions of smaller artists. I walked the platform-like levels and the stairs linking them. Then, I spotted a print on the wall that I knew my wife would love. As I talked to the staff to buy it, I felt so grown up. It was my first time buying a piece of art from a gallery.

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/60 · ISO

3200

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/60 · ISO

3200

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/60 · ISO

400

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/60 · ISO

400

It now hangs opposite our bed in our bedroom.

Empty space where the print used to

be · Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/60 · ISO 100

Empty space where the print used to

be · Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/60 · ISO 100

Aside from the galleries, I also had the chance to go to a more extensive gallery. Tokyo has some vast museums. This one, in comparison, is a bit smaller yet still notable.

The Mori Art Museum is on the 35th floor of the 45-floor Mori building. The building is the crown jewel of the sprawling Roppongi Hills development. I’d already seen the Mori name emblazoned across many a skyscraper and heard the name Roppongi Hills from friends who had spent time in foreign company offices housed there. So, my anticipation was high.

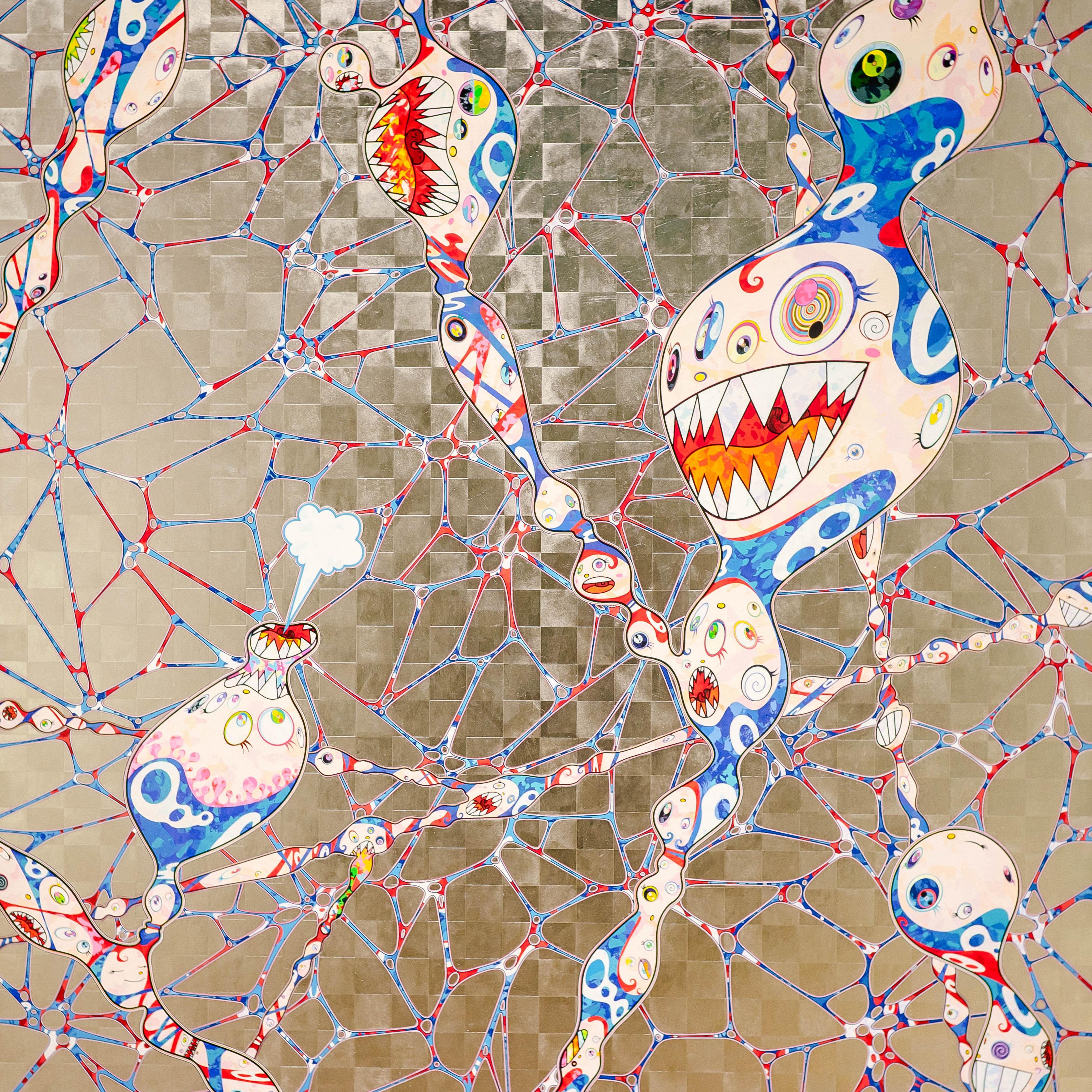

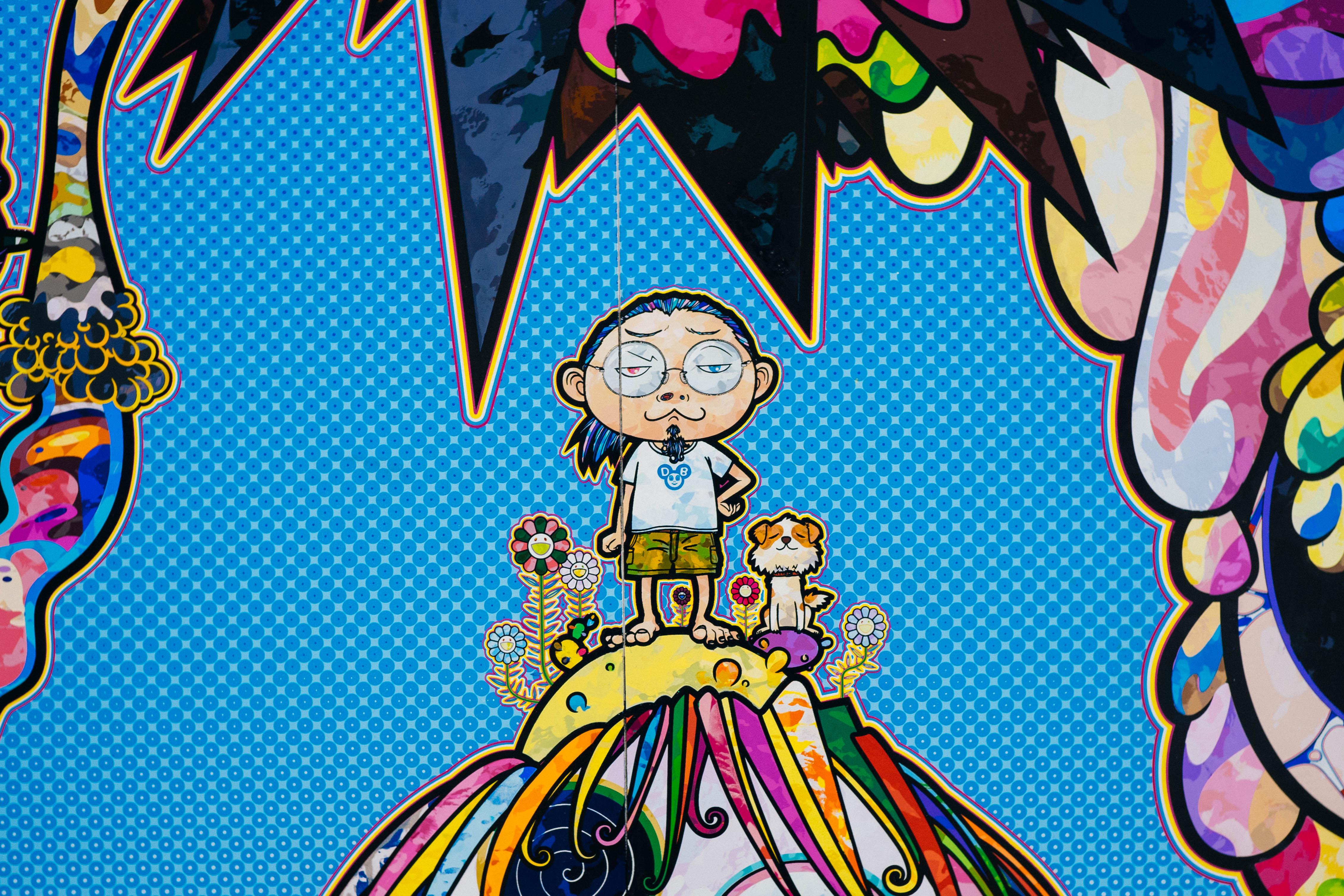

The Mori Art Museum doesn’t have a permanent collection. Instead, it features temporary exhibitions, often of artists from outside Japan. I was pretty happy to see the gallery dedicated that time to the work of a Japanese artist I have admired for a long time, Takashi Murakami.

He has, of course, become quite famous due to his work with idols of fashion, design, and music. Like many other people, I admire him for his liberal borrowing from Otaku culture. The exhibition was titled “Takashi Murakami: The 500 Arhats”.

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/60 · ISO

160

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/60 · ISO

160

The exhibition featured work that mashed up his usual flavor of pop art with traditional Japanese Buddhist imagery. The large-scale paintings featured the motifs and characters he built up over his career but incorporated them into a larger whole, unlike his previous work.

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/60 · ISO

320

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/60 · ISO

320

A self portrait hidden within a

larger work · Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/60 · ISO 160

A self portrait hidden within a

larger work · Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/60 · ISO 160

I read some criticism after the show and was astounded by the negativity. It seemed that some in the art scene wanted him to stay in his corner making Otaku or popular art. Much of the criticism forgot that he is a classicly trained artist that had gone down the path that many accomplished artists before him did. In my eyes, his art is just the latest in the continuously evolving Japanese art scene.

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/60 · ISO

3200

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/60 · ISO

3200

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/50 · ISO

6400

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/50 · ISO

6400

Reconciling this criticism with my overwhelmingly positive impression of the art gave me more confidence. It showed me a way to continue experimenting and pushing through, even in the face of negativity.

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/250 · ISO

100

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/250 · ISO

100

Tokyo Auto Salon

As a side effect of going to Comiket earlier, I became confident going to events in Japan.

Over the years before, I heard about one of these events over and over while reading automotive blogs like Speedhunters — Tokyo Auto Salon.

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/100 · ISO

100

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/100 · ISO

100

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/60 · ISO

3200

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/60 · ISO

3200

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/30 · ISO

6400

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/30 · ISO

6400

It’s like a Japanese version of SEMA in the US. Unlike SEMA, though, Tokyo Auto Salon is open to ordinary people like me. It entertains the broad spectrum of Japanese automotive subcultures. There are drift cars, outlandish bosozoku motorcycles, widened exotic cars from Liberty Walk and RWB, and more.

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/60 · ISO

400

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/60 · ISO

400

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/60 · ISO

2000

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/60 · ISO

2000

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/40 · ISO

6400

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/40 · ISO

6400

I took a short train ride from Shibuya in Tokyo to the Makuhari Messe in nearby Chiba to get there. The convention sprawls throughout multiple halls with aisle after aisle of cars and people. I’d stop to take photos, listen to live musicians, and hear talks given by celebrities.

Japanese director Terry Ito · Sony a7

· 40mm · 1/60 · ISO 250

Japanese director Terry Ito · Sony a7

· 40mm · 1/60 · ISO 250

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/30 · ISO

6400

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/30 · ISO

6400

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/250 · ISO

100

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/250 · ISO

100

Like the cosplayers at Comiket, there were also plenty of models posing by the cars and amateur photographers there to capture them.

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/60 · ISO

250

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/60 · ISO

250

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/60 · ISO

100

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/60 · ISO

100

I even took part in some games. One of them was a gashapon machine that offered a slim chance of winning a grand prize. I put my two hundred yen expecting nothing. To my surprise, a ball returned with a red slip of paper indicating that I had won the prize.

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/250 · ISO

100

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/250 · ISO

100

I happily took it back to the owners of the gashapon machine, and they exchanged the slip of paper for an intricate model of the Ferrari F40, which has been one of my favorite cars since a young age.

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/200 · ISO

100

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/200 · ISO

100

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/60 · ISO

640

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/60 · ISO

640

This event was huge. By the time I walked through all the exhibition spaces, my legs were tired. On the ride home in the afternoon, I felt a deep sense of inspiration from seeing so many objects crafted through pure passion.

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/60 · ISO

320

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/60 · ISO

320

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/160 · ISO

100

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/160 · ISO

100

Public transportation

After I toured the local art and Tokyo Auto Salon, I started to see a pattern. The ethos of Japanese design, that careful amalgamation of old and new, is manifested in every detail of the built environment. No aspect shows this more than public transportation.

For example, there’s the music. I noticed that nearly every train station has unique songs for when a train arrives and departs. They help those with limited eyesight or literacy get off at the right stop. Over time I grew accustomed to the songs at my home station and the bigger main stations. Often, I would get off the train without looking up.

Another piece of transportation in Japan that I grew to love is the humble IC card.

Each region has a set of transit cards in Japan. In Tokyo, the most famous are Suica, issued by the Japan Rail, and PASMO, issued by the Tokyo Metro. On the inside, each of these cards is maintained by a different transit authority. However, because they use the same technology and interoperability agreements between the transit authorities, they can be used interchangeably.

I used my PASMO card to take the subway, pay at restaurants and convenience stores, lock and unlock coin lockers, and more. My PASMO felt like a magic do-everything-device the way smartphones feel.

On my latest trip to Japan in early 2020, I forgot my PASMO at home and signed up for a Suica on my iPhone. I did sorely miss the feeling of holding the physical card in my hand. However, Apple Pay was quite convenient. And let’s not forget that the magic is still there. With an IC card in hand, you can go nearly anywhere.

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/60 · ISO

500

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/60 · ISO

500

I do mean anywhere. Japan is one of those places where you can go to almost any city or town just using public transportation. There are multiple different options between popular places differing in speed, convenience, and cost.

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/60 · ISO

1250

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/60 · ISO

1250

My formative years as an adult were spent in New York City, where I went to school. I got a taste of what’s possible when you can get nearly anywhere within a metropolis 24/7. Of course, there’s a lot to be desired with New York’s aging system.

In Japan, however, the transit systems are emblematic of what Japan does so well. The stations are immaculate. Trains are always on time. Famously, some of the operators in Japan will offer refunds if they make their passengers late.

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/160 · ISO

100

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/160 · ISO

100

I was heavily reliant on Google Maps while getting around Tokyo. I found that Google Maps in Japan indicates not just the overall route but exactly which entrances and exits to take. It even draws pathways throughout the maze-like underground stations.

Near the end of my time in Tokyo, I packed up to head to Kyoto. I’ll go into more detail in my following essay, but I have to talk about one aspect of it, how I got there. At Tokyo Station, I got on a bullet train, or shinkansen, specifically an N700 on the Tokaido line.

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/1250 · ISO

100

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/1250 · ISO

100

The Tokaido Shinkansen takes its name from a historical road which it roughly follows. That road was the most important of the five roads connecting major cities during the Edo period. This line was the first shinkansen, and it served as a model for the rest of the shinkansen system all around Japan.

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/500 · ISO

500

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/500 · ISO

500

To foreigners, the entire train system can sometimes be a little confusing. Unlike many other countries where regional trains all use the same rolling stock and terminology, the shinkansen is unique in every region. Some trains only run on specific lines and in certain areas. Even trains used on multiple lines like the N700 are painted differently.

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/500 · ISO

800

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/500 · ISO

800

To add to the complication, JR, or Japan Rail, is a series of seven separate companies that operate together as the Japan Railways Group.

Current and future

shinkansen routes. each color represents a different JR company

Current and future

shinkansen routes. each color represents a different JR company

While going to Kyoto, I stopped at the SCMaglev and Railway Park. This is a large building dedicated to bullet trains in Japan. It’s named after the SCMaglev, a project that aims to offer a faster magnetic levitation option between Tokyo and Osaka, the busiest transportation corridor in Japan.

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/60 · ISO

6400

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/60 · ISO

6400

After spending the afternoon at Railway Park, I returned to my bags, which I had stored in a locker with my PASMO, and boarded a Shinkansen headed toward Kyoto.

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/60 · ISO

4000

Sony a7 · 40mm · 1/60 · ISO

4000

As the train gently accelerated, the buildings out the window turned into blurs and gave way to fields. My compartment was mostly empty, the only sound being the low hum of the electric motors. I started to reflect on the past few weeks. I realized that I felt more perceptive than before. As I noticed more examples of great design, a switch in my head flipped.

At that point, I was working at a startup in a domain that I had little interest in with people that didn’t understand me.

I was starting to gravitate away from engineering and towards design, which at that point was just a hobby, not something I considered seriously as a profession.

As we pulled into Kyoto Station, I had a realization — I had to leave and take my career elsewhere.

Thanks to Q for reading drafts of this.