This is part three of the series about my first trip to Japan.

In part one, I was with friends who had extensive experience getting around Japan. They showed me the ropes while we attended Comiket and enjoyed the hot springs in Hakone. In the second part, I stayed in Tokyo by myself, exploring the art and automotive cultures. I started to realize that I needed to change my life.

Kyoto

During the rise of the Tokugawa shogunate, the center of Japan moved to Tokyo, then called Edo. It grew for nearly half a millennium before being mostly leveled during the firebombing during World War Two. Over one hundred thousand civilians died in an event that many historians say should be considered a war crime.

That kind of firebombing across Japan erased over one millenium of history. Buildings that had been preserved for centuries were destroyed.

It’s when pondering this thought that I realized why Tokyo felt so modern. Most of the city was constructed in the last half-century.

There is one notable exception to this pattern of destruction, Kyoto. The former capital before Edo, it was founded more than 1200 years ago. It was spared from the large-scale destruction that befell most of Japan’s other cities. Kyoto remains a cultural center of Japan and a prime site for tourists.

My experience in Kyoto was different than my time in Tokyo. The pace felt a lot slower. People didn’t walk as quickly. I didn’t see as many business people in suits, carrying briefcases.

I first checked out Kyoto Tower. The observation deck didn’t look too high off the ground but was tall enough to tower over the rest of the ancient city. Surprisingly, there weren’t other foreigners. Just a few domestic tourists joined me in enjoying the panoramic views.

I then went over the Fushimi Inari-Taisha, Kyoto’s most famous Shinto shrine. It was there that I saw the first large group of tourists. Bus after bus filled the parking lot leading up to the shrine’s entrance.

I started exploring and soon found myself at the Senbon Torii. They are a set of torii gates that people and organizations started to donate to the shrine hundreds of years ago. In return for their donations, they wish for good fortune.

Now, more than a thousand gates line the paths up the mountain. I walked up the slope, which started gradually but became steeper and steeper. Within minutes, I had lost the other tourists who undoubtedly had a tight schedule.

It was just me, the forest, and a long line of red gates. I pondered the topic on my mind since the moment I entered Kyoto. What did I want to do with my life?

I realized that I was scared. I had an engineering degree from a top university. My credentials opened a lot of doors for me.

However, the strength of that reputation was holding me back. It was the source of the voice in my head telling me that I couldn’t be a designer. I should stay an engineer. I should stick to what I’m good at.

All those designers I would meet at events in San Francisco had different credentials. They were product designers at prominent companies or had degrees from top art and design schools. How could I compete with them?

I pondered this topic as I continued walking through the old part of Kyoto. I experienced a city from before post-war modernization. Again, there were plenty of tourists.

To find some solitude, I would take a sidestreet. Within minutes, I was alone yet still surrounded by beauty.

I sat near the purification fountain in front of a small shrine. The sound of running water brought clarity to my mind. I looked around and could only describe my surroundings as having been designed well. The buildings were orderly yet showed signs of age. The gardens were clean yet organic. The people who created this place indeed had immense skill — skill that came not from credentials, but from lifetimes of experience and learning from masters.

And so, I realized that not only did I need to quit, I needed to act. The only way forward was to do the work. I had to forge my own path.

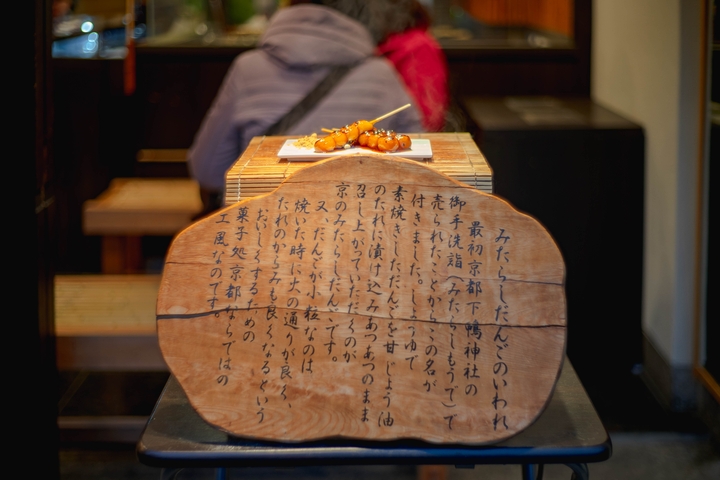

As I walked, I sampled some of the local delicacies. One of my favorites is Mitarashi Dango, little balls of riced flour dipped in a sweet soy sauce reduction.

I also sampled a form of sushi specific to the region, oshizushi. Up until that point, I only had eaten Edomae (Edo-style) sushi. It’s the kind we’ve all seen before, cuts of fish draped over a ball of rice. In oshizushi, the rice and fish are tightly packed together and then cut into pieces. It was pretty delicious!

Kyoto at night

As the sun set and day became night, the city transformed.

These days, when people picture the Japanese aesthetic, they probably have Muji in mind. They see bright open spaces, white walls, and light-colored woods accented with touches of silver.

The traditional Japanese aesthetic is far from that. Ripe with colors from the natural world, it embraces the contrast between light and shadow. In Praise of Shadows, an essay by Jun’ichirō Tanizaki, expounds on the distinction between the traditional Japanese aesthetic and the ever more popular Western aesthetic. It was written in the early Shōwa period when Western culture took Japan by storm.

I sensed the traditional aesthetic first hand at night in the older part of the city. Streets were dimly lit by lights similar in color to candles. The road surfaces were set in dark gray stone. The buildings were primarily framed in dark wood with light brown walls. It was a setting that was again perfect for pondering the life ahead of me.

At the end of my time in Kyoto, I was already feeling more certain about my future. Being in a city with so much history and beauty made my worries seem small.

I didn’t have a chance to see all of what the ancient city offers, but I knew I’d be back soon. Next up in the trip for me was Hiroshima. Read more in the final essay of this series.

Thanks to Q for reading drafts of this.