Staying at the TWA Flight Center

8 min read Apr 13, 2022

The airport terminal — once a humble place like a bus stop or train station soon became a symbol of pride. Some, like Singapore’s Changi, have become destinations themselves.

Most large cities around the world boast airports fitting their splendor. Large vaulted ceilings clad in steel and glass fit the spectacle of flying. How could you not like the grandeur of it all? The idea of hurdling thousands of miles across our globe in perfectly engineering metal tubes requires some fanfare.

So I’m always surprised when I arrive in New York — a place I consider the center of the world. I’m greeted by none of what I just described. New York’s airports don’t sugarcoat the New York experience. They are as crowded, filthy, and inconvenient as its subway stations. But I wouldn’t have it any other way.

All it takes is one glance at the Manhattan skyline while landing. Gone is the dread of the crowded arrival hall and the Taxi line. Listen closely around you, and you’ll notice a smattering of languages from around the world. Even though they are outdated and unpleasant, the airports in New York are the melting pot of the world and the gateway to a cultural epicenter.

So it is only fitting that when you arrive at JFK’s JetBlue terminal, you are treated to something special across the street. It’s an architectural marvel — the TWA Flight Center. Nestled within the arc of the modern JetBlue structure, the terminal lies, its two concrete roofs extending out like wings. Two spindle-like tunnels connect to the newer building. They trace a path travelers once took decades ago.

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/8 · 1/750 ·

ISO 160

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/8 · 1/750 ·

ISO 160

I noticed it year after year when I went to college in New York but never once stepped inside. It had closed by the time I arrived. Then, years later, I was fortunate enough to visit during Open House New York. At the time, its fate was still undetermined. While its landmark status prevented demolition, previous plans to reuse it as an airport terminal had fallen through. Then, plans came together, and construction started. It became a hotel.

We were supposed to go there for a wedding, but it was delayed repeatedly as the pandemic surged. Finally, the wedding happened in the rare post-vaccine lull of 2021. My wife and I decided to forgo our usual habit of staying in Manhattan and stay at the TWA Hotel for the duration of the wedding.

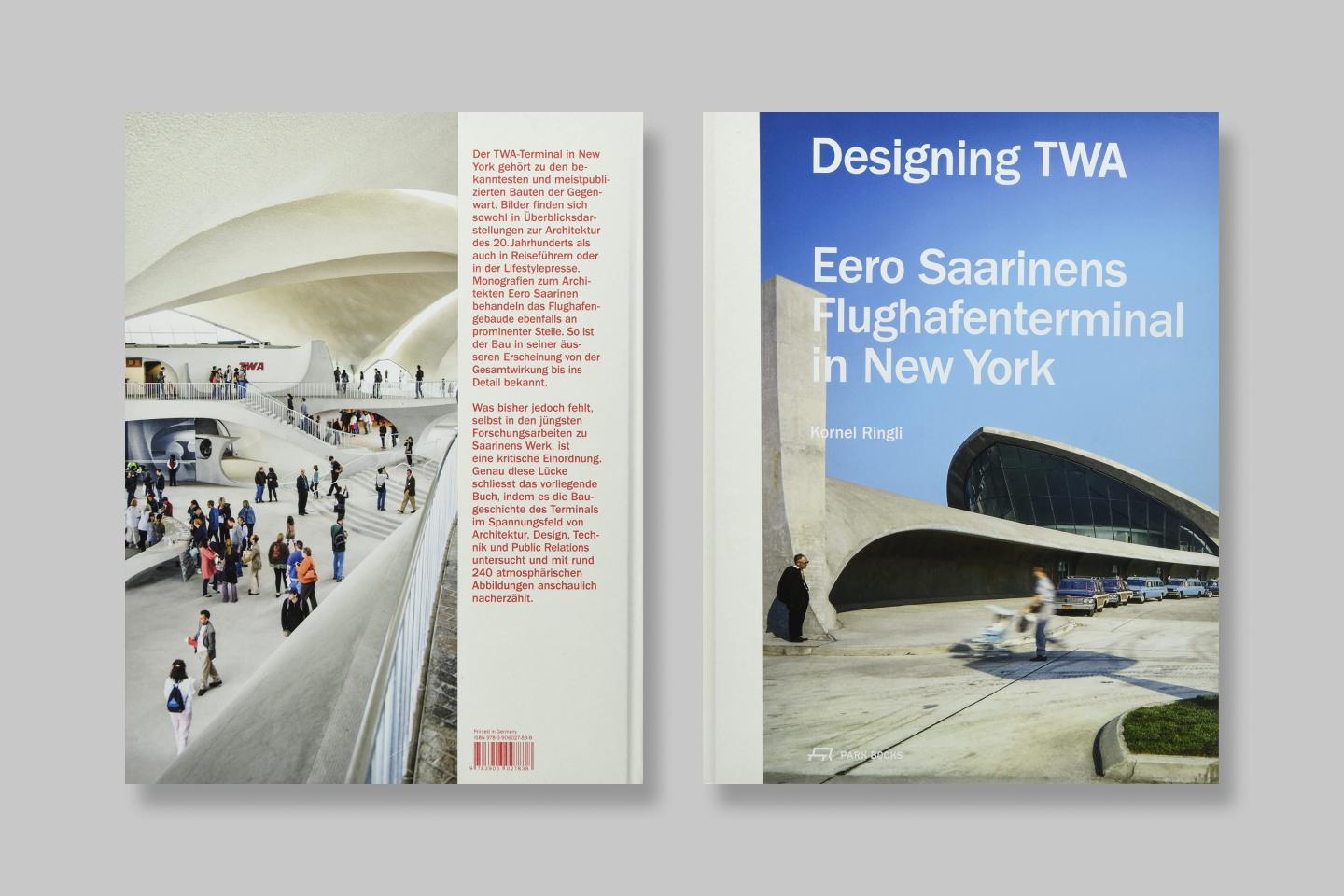

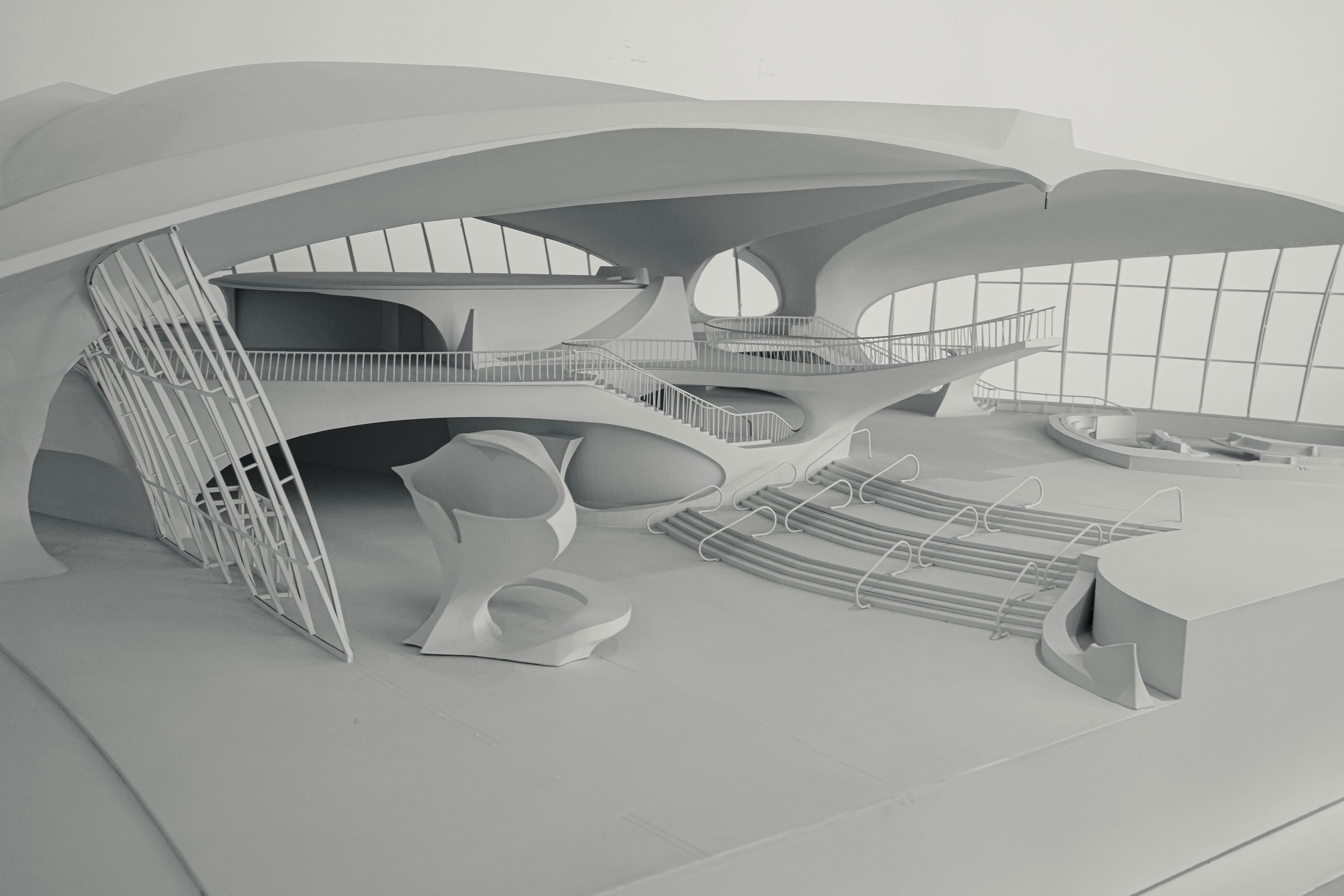

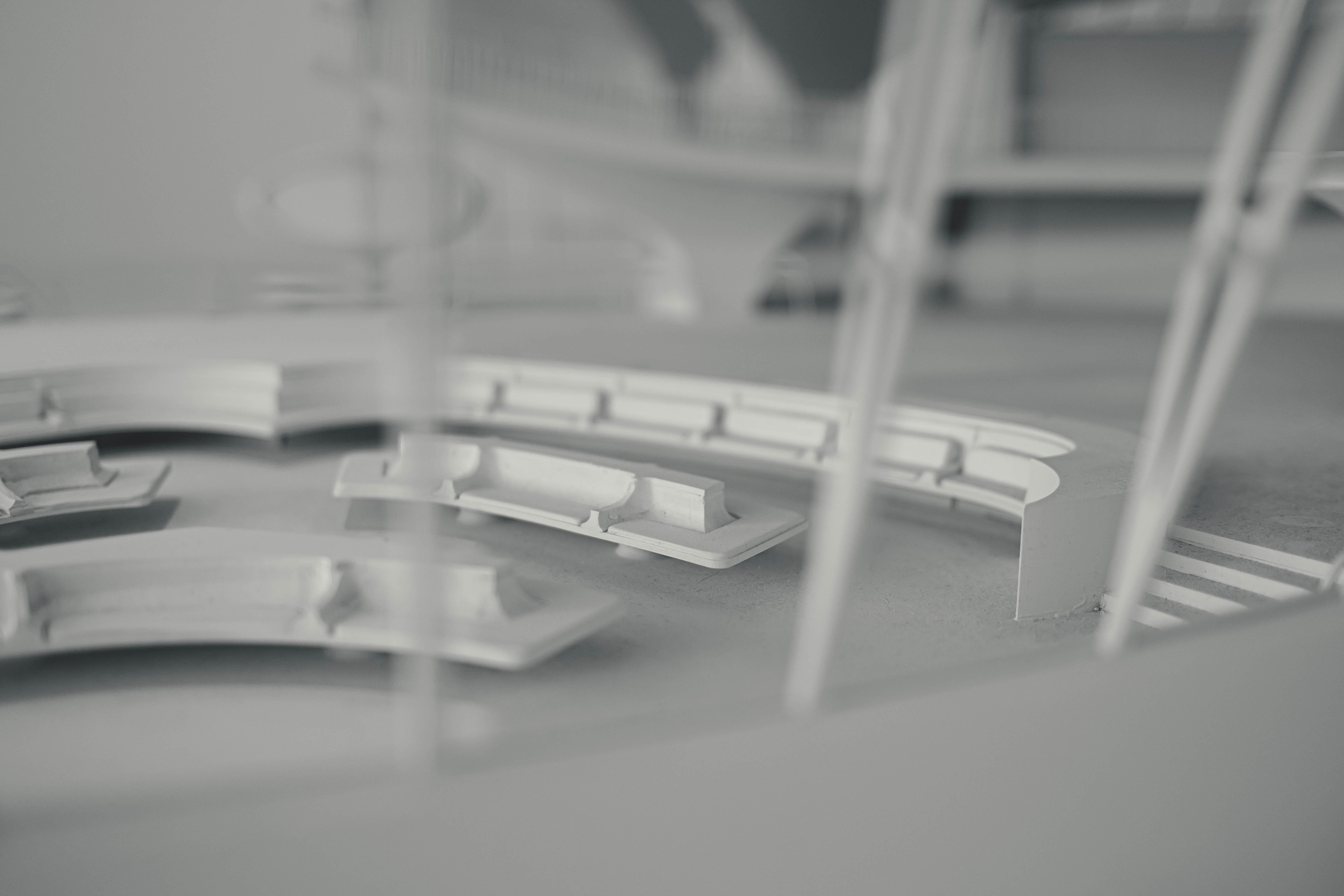

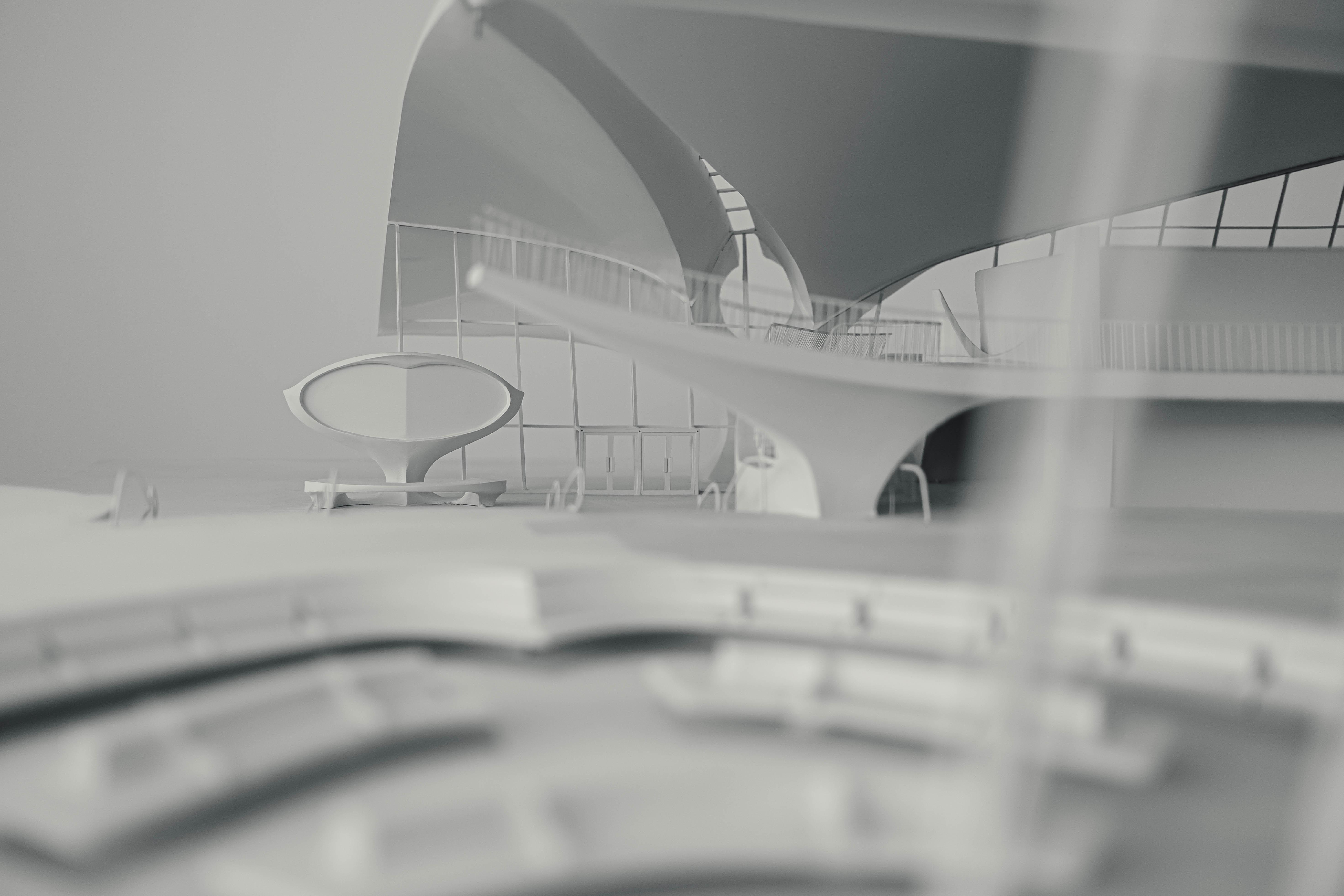

Designing TWA

Since I officiated the wedding, the bride and groom gave me a copy of Designing TWA as a gift. The book is everything I could have hoped for. There are beautiful photographs, sketches from various stages of the project, and of course, the raw details and history of the building.

The book is divided into three parts. The first sets the stage. Idlewild Airport (later renamed to JFK) had opened in 1948 and operated with just one terminal and tower.

To fit the rapidly growing airlines like TWA, Pan Am, American, etc., the “Terminal City” plan was unveiled. It called for each major airline to design and build its own terminal while smaller airlines operate out of a large international terminal. You have this plan to blame if you ever wonder why JFK feels sprawling and disconnected.

A postcard from the early

60s

A postcard from the early

60s

Form following function

Each terminal had its unique style, including one of my other favorites, Pan Am’s Worldport. The saucer-like roof created a canopy underneath which smaller narrow-body aircraft would park. Unfortunately, it was demolished recently.

Source: Life Magazine

Source: Life Magazine

These architectural styles were part of a broader trend. Corporations had realized the edge that brand identity gave them. So, they saught designers to craft logos, iconic buildings, and even the exact path the people took through those buildings.

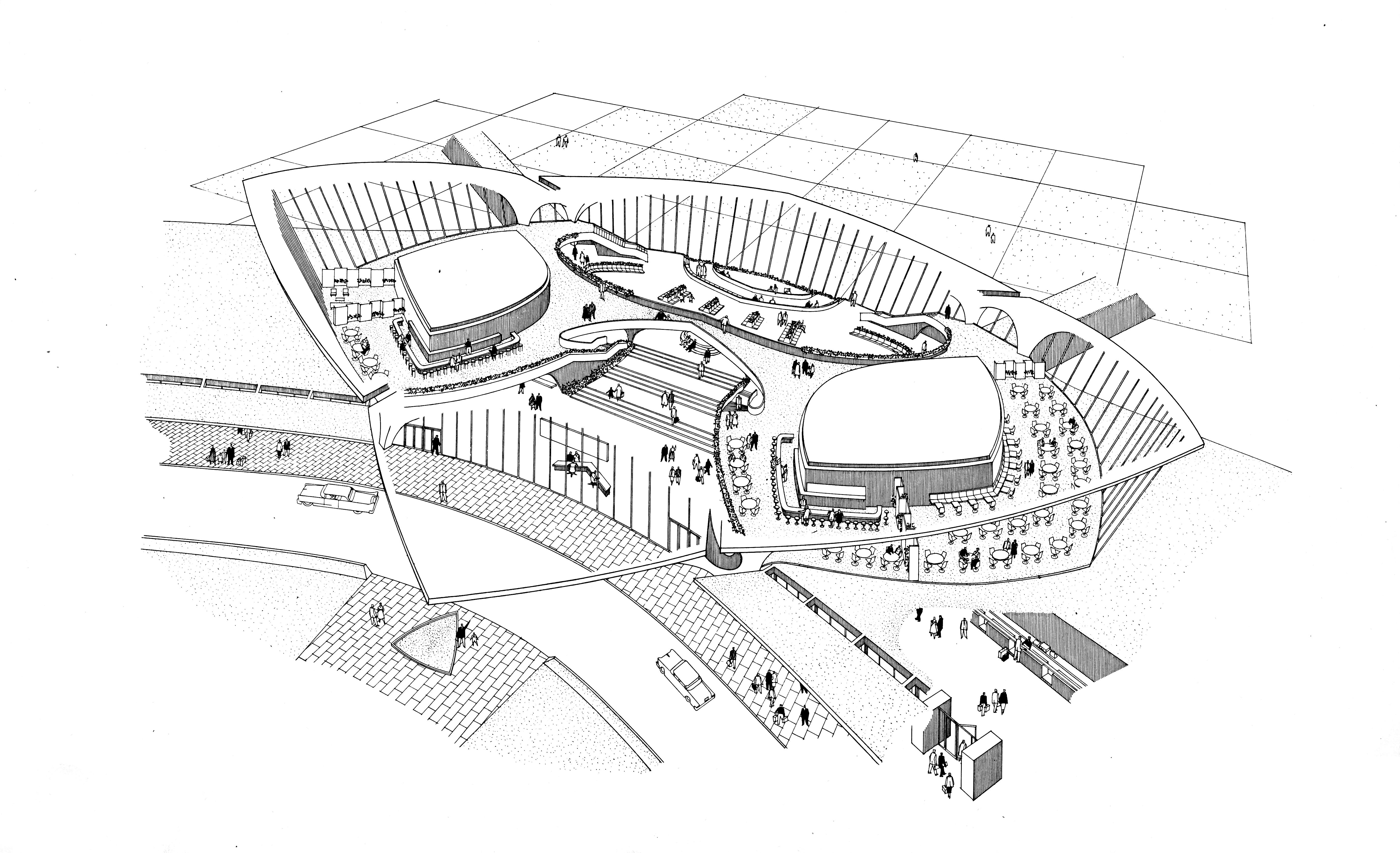

The TWA Flight Center was no different. The building sought to concretize the business processes of the airline. Early drawings in the book show flow diagrams later translated into floorplans. The goal was efficiency.

Source: Library of Congress

Source: Library of Congress

This design method may have ultimately led to the failure of the TWA Flight Center, Pan Am Worldport, and other terminals. The flow diagrams mirrored processes existent in the 1950s — processes that would rapidly change with the introduction of jet aircraft like the double-decker Boeing 747. These larger, faster aircraft meant that every piece of the airline’s operations would burst out of its seams. Their buildings were too small and hence failed.

So you may be wondering how the TWA Flight Center survived demolition.

Form as a differentiator

The second section of the book explains how this building became iconic.

As I mentioned earlier, the airlines, like other corporations, had realized the value of architecture. At its opening in 1962, TWA’s Flight Center immediately failed to fulfill the promises of efficiency it was designed around. However, it succeeded in becoming a symbol.

Four years earlier marked a significant turning point. Lockheed ceased production of the Constellation, TWA’s most prominent corporate symbol. In the same year, Boeing started to deliver its first jetliner, the 707, ushering in the jet age.

Lockheed Connstellation. Source:

NACA · Ames Imaging Library System

Lockheed Connstellation. Source:

NACA · Ames Imaging Library System

So, while TWA’s propeller-powered symbol lost its potency, a building, not another airplane, replaced it.

The public image

The last section mentions how TWA’s symbol ingrained itself into American culture.

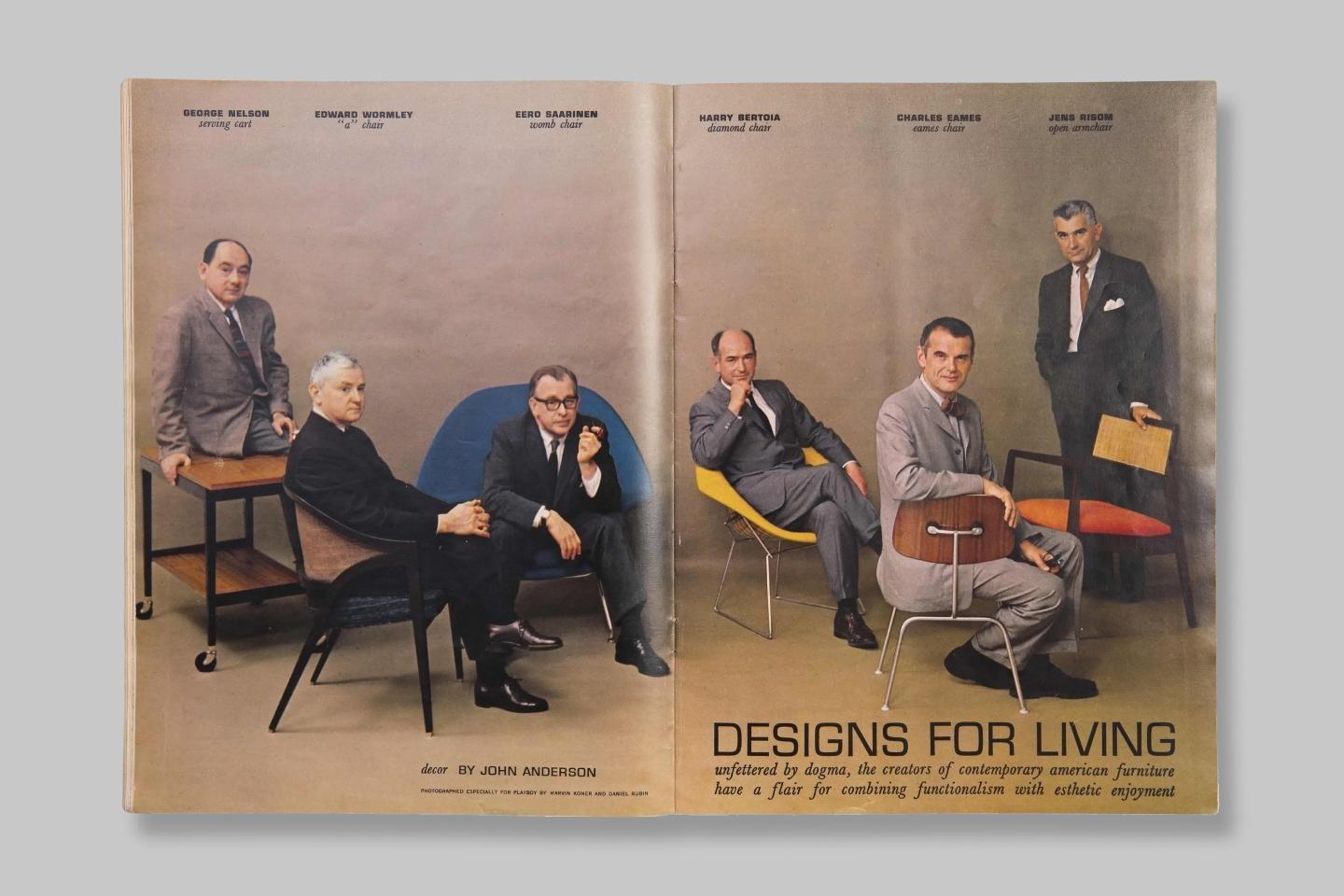

Eero Saarinen, the building’s architect, was primarily known as a furniture designer. He had higher ambitions. That’s where his wife, Aline Saarinen, comes in. She used her experience and contacts from her former life as a New York Times journalist to propell her husband into fame.

There’s no more proof needed than the spread from a 1961 Playboy magazine titled Designs for Living. In it, Saarinen is seated in his Womb Chair next to other contemporary design greats, each with their own chairs.

George Nelson, Edward Wormley, Eero

Saarinen, Harry Bertoia, Charles Eames, Jens Risom

George Nelson, Edward Wormley, Eero

Saarinen, Harry Bertoia, Charles Eames, Jens Risom

So, as Saarinen and his building gained notoriety, TWA did as well. Soon, the flow diagrams and promises of efficiency are all but forgotten. What remained is an iconic building shaped like no other. Over time, it found its place in the pantheon of architecture alongside works by other iconic architects like William Van Alen, Le Corbusier, and Frank Lloyd Wright.

My experience

If you are interested in more, I recommend checking out Designing TWA.

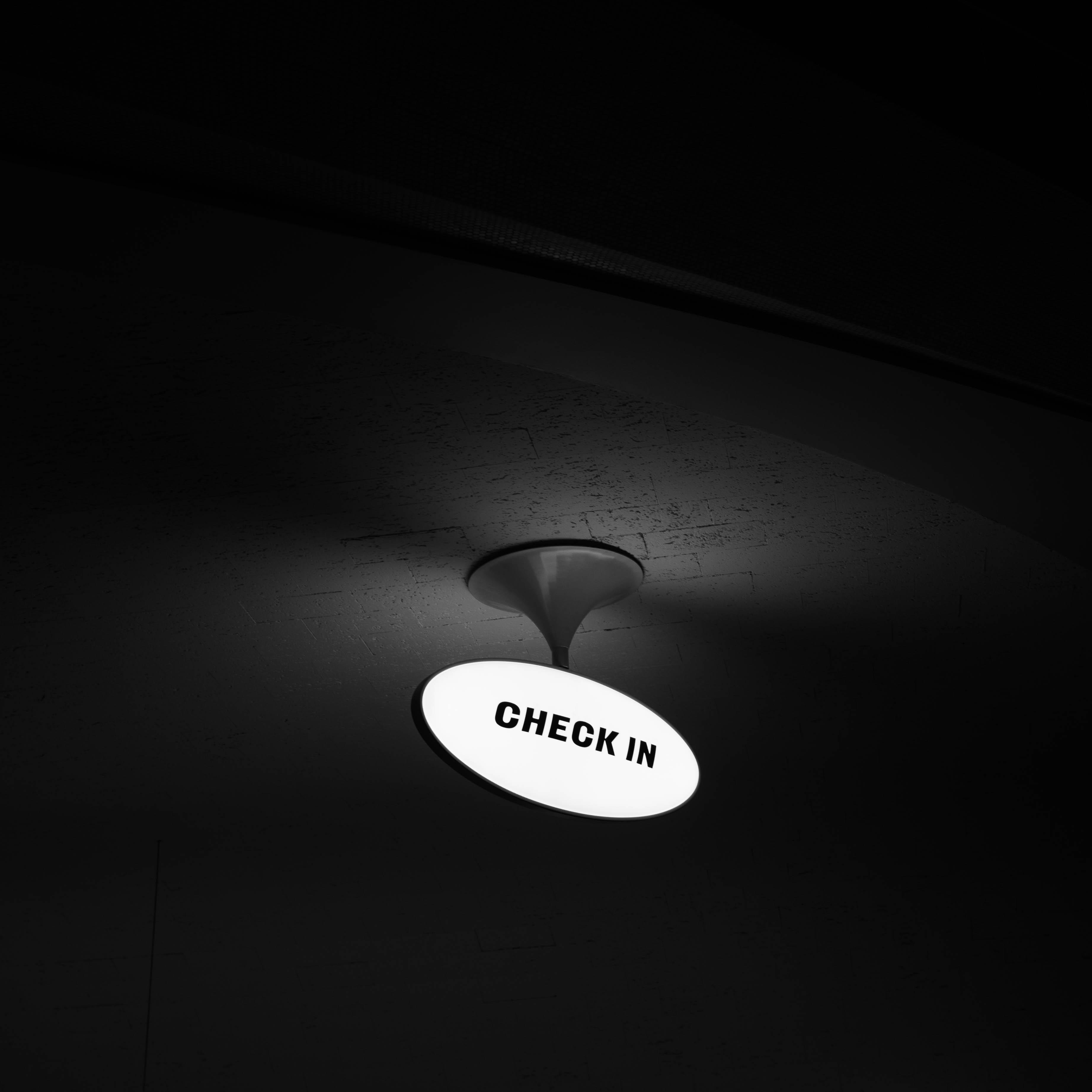

I won’t give the hotel a full review but will say one thing. If you have an extended layover or late flight landing in JFK, consider staying at the TWA Hotel. Grab a cocktail at the bar and walk around the mid-century architectural marvel. Enjoy an espresso in the early morning as weary travelers rush into the terminal nearby. You won’t regret it.

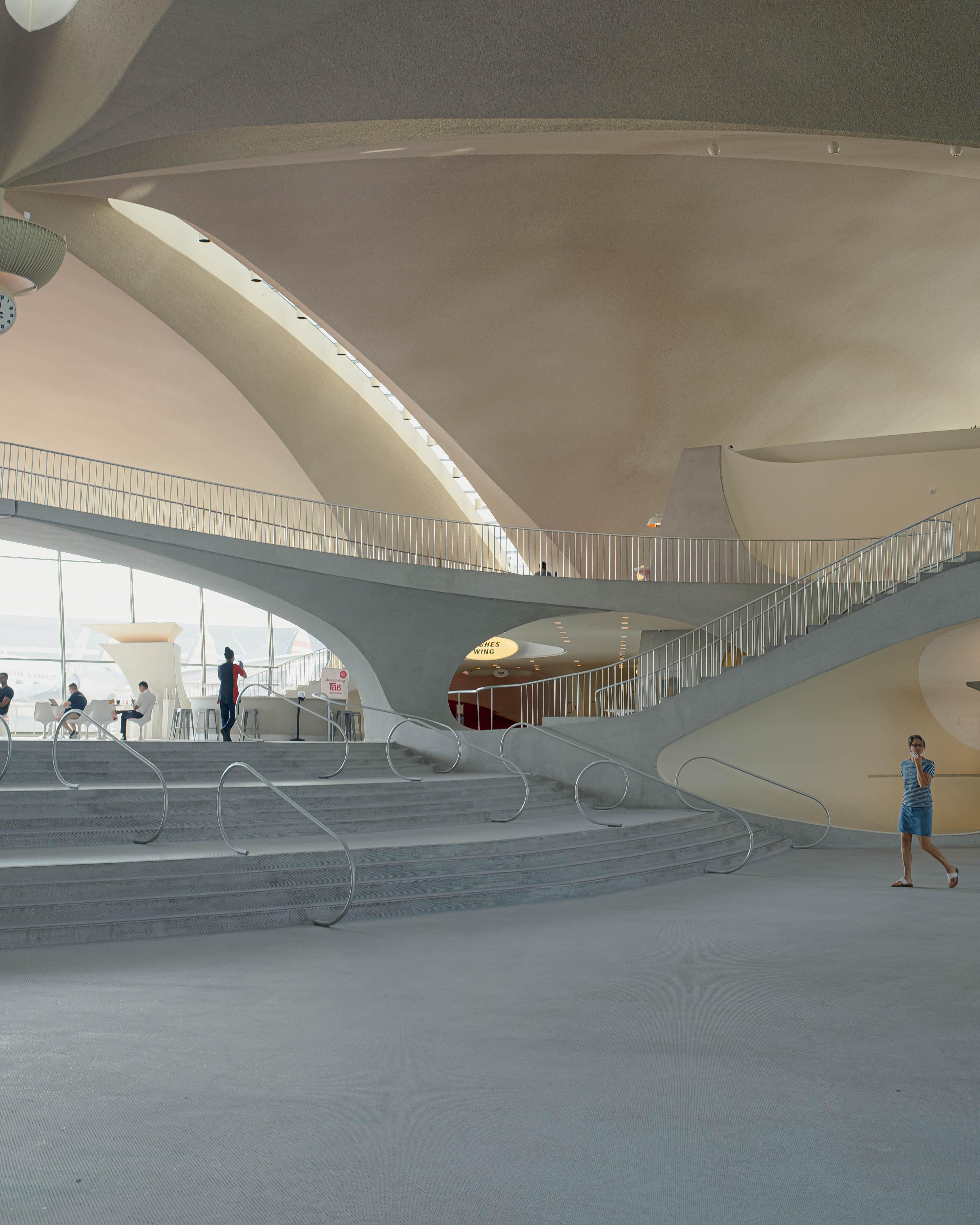

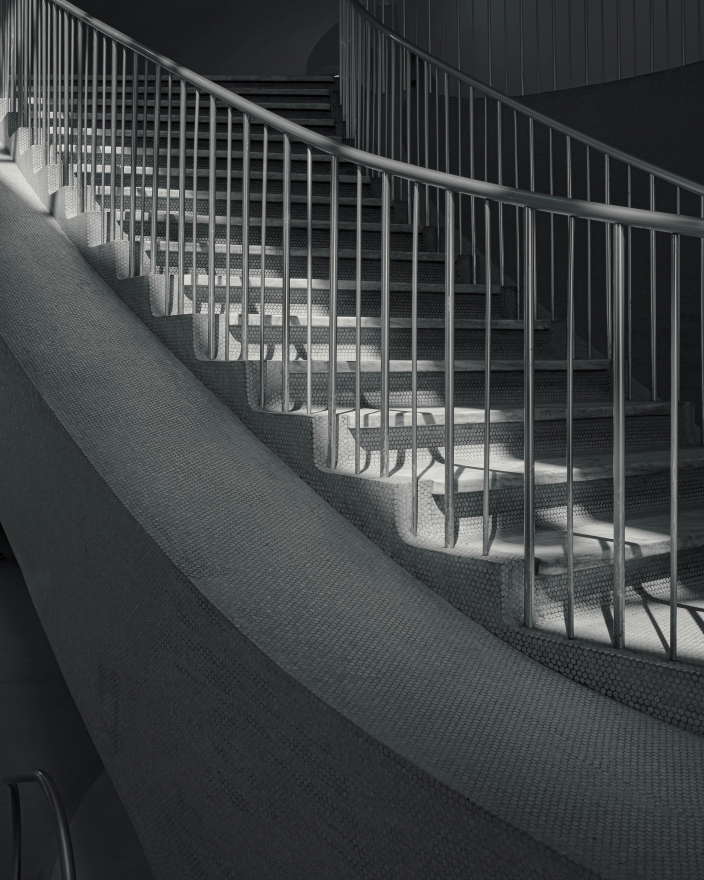

Lastly, I hope you enjoy the photos I took during my three days at the TWA Flight Center. I captured them on the Fujifilm X100V that I still owned at the time. We were lucky to receive some rain on one day. So we saw the terminal in a variety of lighting conditions.

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/10 · 1/60 ·

ISO 800

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/10 · 1/60 ·

ISO 800

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/3.2 · 1/60

· ISO 320

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/3.2 · 1/60

· ISO 320

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/2 · 1/60 ·

ISO 400

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/2 · 1/60 ·

ISO 400

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/2 · 1/60 ·

ISO 2500

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/2 · 1/60 ·

ISO 2500

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/2 · 1/60 ·

ISO 640

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/2 · 1/60 ·

ISO 640

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/2 · 1/60 ·

ISO 800

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/2 · 1/60 ·

ISO 800

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/2 · 1/60 ·

ISO 1000

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/2 · 1/60 ·

ISO 1000

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/4 · 1/1250

· ISO 160

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/4 · 1/1250

· ISO 160

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/9 · 1/60 ·

ISO 320

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/9 · 1/60 ·

ISO 320

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/3.6 · 1/240

· ISO 160

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/3.6 · 1/240

· ISO 160

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/3.6 · 1/110

· ISO 160

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/3.6 · 1/110

· ISO 160

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/2 · 1/60 ·

ISO 200

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/2 · 1/60 ·

ISO 200

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/2 · 1/90 ·

ISO 160

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/2 · 1/90 ·

ISO 160

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/2 · 1/200 ·

ISO 160

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/2 · 1/200 ·

ISO 160

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/2 · 1/150 ·

ISO 160

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/2 · 1/150 ·

ISO 160

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/5 · 1/320 ·

ISO 160

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/5 · 1/320 ·

ISO 160

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/10 · 1/60 ·

ISO 160

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/10 · 1/60 ·

ISO 160

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/8 · 1/60 ·

ISO 800

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/8 · 1/60 ·

ISO 800

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/2 · 1/220 ·

ISO 160

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/2 · 1/220 ·

ISO 160

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/2 · 1/200 ·

ISO 160

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/2 · 1/200 ·

ISO 160

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/8 · 1/1500

· ISO 160

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/8 · 1/1500

· ISO 160

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/8 · 1/1500

· ISO 160

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/8 · 1/1500

· ISO 160

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/4 · 1/1000

· ISO 160

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/4 · 1/1000

· ISO 160

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/4 · 1/60 ·

ISO 500

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/4 · 1/60 ·

ISO 500

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/4 · 1/60 ·

ISO 250

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/4 · 1/60 ·

ISO 250

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/10 · 1/60 ·

ISO 320

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/10 · 1/60 ·

ISO 320

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/3.6 · 1/90

· ISO 160

Fujifilm X100V · 23mm · f/3.6 · 1/90

· ISO 160

Thanks to Q for reading drafts of this.