The tale of two Shanghais

7 min read Dec 15, 2024

As an adolescent, I used to be obsessed with skyscrapers. I made daily visits to the Skyscraper City forums, eagerly waiting for progress photos as supertall skyscrapers went up around the world.

I was lucky to visit Shanghai with my family in 2005, just as Shanghai’s skyline was rapidly changing. I previously wrote how the cars on the road in China have been a visual indicator of economic progress over my visits in the last two decades. A similar story can be told through the architecture.

Shanghai is the largest of the many major cities concentrated around the Yangtze Delta. Unsurprisingly, water is a major geographical influence on how that area has been populated over the millennia. For example, Wuzhen, Suzhou and many other towns in the area are crisscrossed by canals much like Venice. The West Lake, a massive freshwater lake in Hangzhou, has been a tourist destination for nearly 1500 years.

In Shanghai, the Huangpu River is the major geographical feature, dividing the city into Puxi on the west and Pudong on the east. Till recently, the two sides of the river have had vastly different patterns of development. Take a river boat on the Huangpu River, and the difference will be obvious.

Following the First Opium War and the signing of the Treaty of Nanking in 1842, Shanghai was opened up as one of five treaty ports in China. This resulted in settlements being constructed in Puxi by various western powers. As a result, the Puxi side of the river is flanked by The Bund, a historical waterfront almost entirely populated by low-height European-style buildings clad in stone.

The Pudong side of the river is today entirely defined by modern glass-clad supertall skyscrapers, but that is a recent development.

Leica Q · 28mm · f/5.6 · 1/500 ·

ISO 100

Leica Q · 28mm · f/5.6 · 1/500 ·

ISO 100

Until the late 20th century, Pudong was only accessible by ferry from the more populated Puxi side. Pudong stayed a rural area used mostly for agriculture and warehousing. In 1990, Pudong was designated a Special Economic Zone (SEZ), spurring rapid development.

In our latest trip to Shanghai last year, we had a chance to visit Pudong and its supertalls yet again.

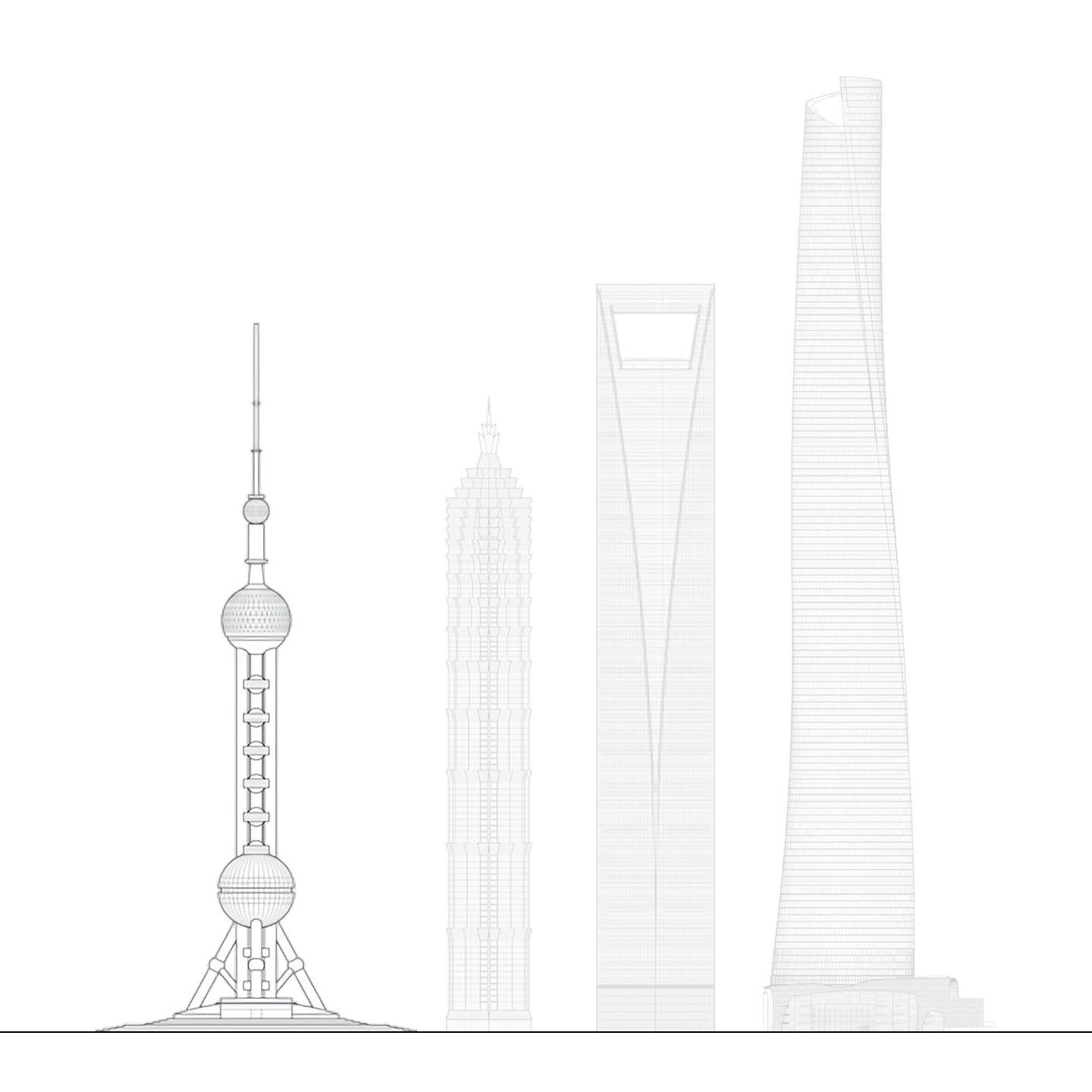

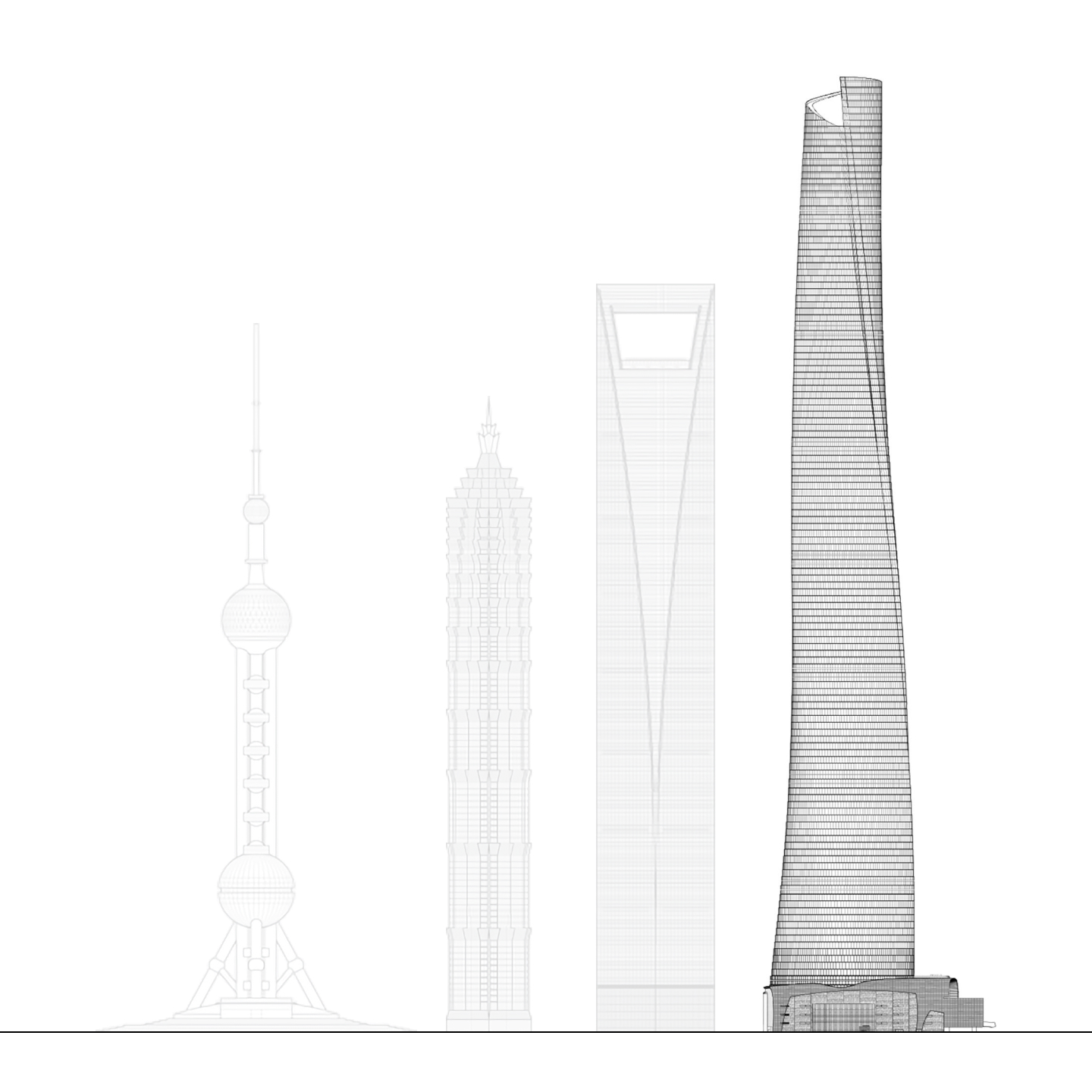

Oriental Pearl Tower

1990 - 1994

468 m / 1,535 ft

342 m / 1,122 ft

10th tallest

The first of the many supertall structures constructed in Pudong is the Oriental Pearl Tower. It was built to support TV broadcast antennas. Construction began just one year after Pudong’s designation as a SEZ and finished three years later in 1994. My wife remembers seeing it out of her apartment window as a child until taller buildings eventually obscured the view.

Leica CL · 56mm · f/5.6 · 1/400 ·

ISO 100

Leica CL · 56mm · f/5.6 · 1/400 ·

ISO 100

I visited it in 2005 and distinctly remember the state of Pudong at the time. Cranes were everywhere as multiple giant developments were all underway.

Leica CL · 56mm · f/5.6 · 1/320 ·

ISO 100

Leica CL · 56mm · f/5.6 · 1/320 ·

ISO 100

This building remained the tallest structure in China until 2007’s completion of the World Financial Center next door.

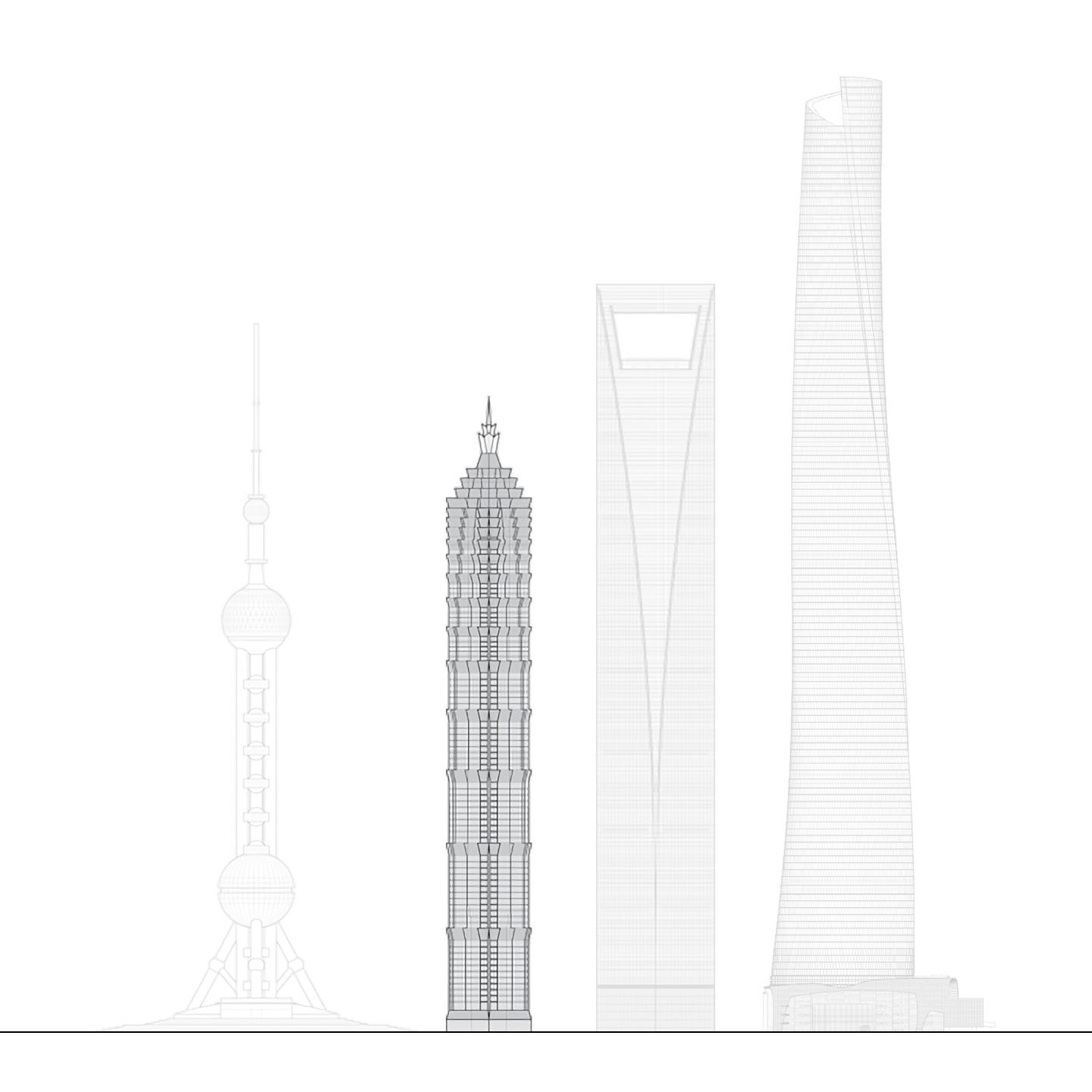

Jin Mao Tower

1994 - 1999

420.5 m / 1,380 ft

348.4 m / 1,143 ft

34th tallest

The Jin Mao Tower, alongside Taipei 101, is one of my favorites in Asia. Both are heavily inspired by traditional Chinese architecture. Designed by SOM, the Jin Mao tower features a faceted exterior that steps back and increases in complexity as the floors rise. The proportions are dictated by mathematical formulas that give it balance.

Leica CL · 18mm · f/5.6 · 1/320 ·

ISO 100

Leica CL · 18mm · f/5.6 · 1/320 ·

ISO 100

I still hope to one day stay at the Grand Hyatt inside, which spanning the 53rd to 87th floors of the 88-floor building, was the highest hotel in the world for a long time.

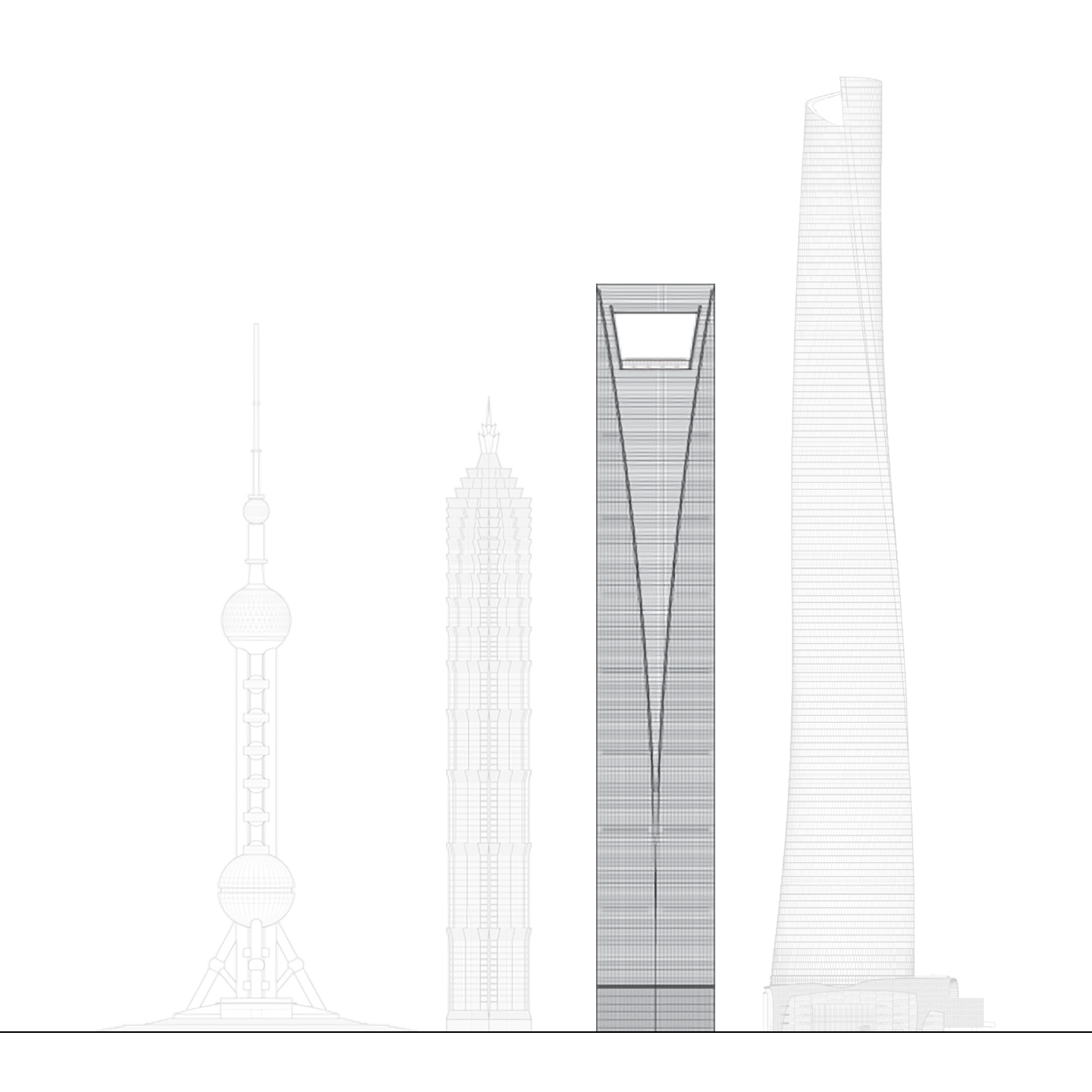

Shanghai World Financial Center

1997 - 2008

494.3 m / 1,622 ft

474 m / 1,555 ft

12th tallest

The Shanghai World Financial Center (WFC) was long in the works. Construction began in 1997, just four years after the Jin Mao Tower. Yet, because of the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis, construction was paused.

Leica CL · 18mm · f/5.6 · 1/200 ·

ISO 100

Leica CL · 18mm · f/5.6 · 1/200 ·

ISO 100

When I visited Shanghai in 2005, construction had again resumed. I looked out from the Jin Mao in awe at the central core under construction. It was just like a photograph I had seen on the Skyscraper City forums. I also distinctly remember seeing souvenir statues of the building offered up at the Pearl Tower gift shop. Those miniatures featured a circular cutout resembling a moon gate. Later that year, after protests by people who claimed the circle looked like the rising sun of Japan, the cutout was redesigned into a trapezoid.

Leica CL · 56mm · f/5.6 · 1/200 ·

ISO 100

Leica CL · 56mm · f/5.6 · 1/200 ·

ISO 100

I believe the trapezoidal cutout is bland. However, the building is still beautiful overall. There are multiple observation decks, both below and above the cutout.

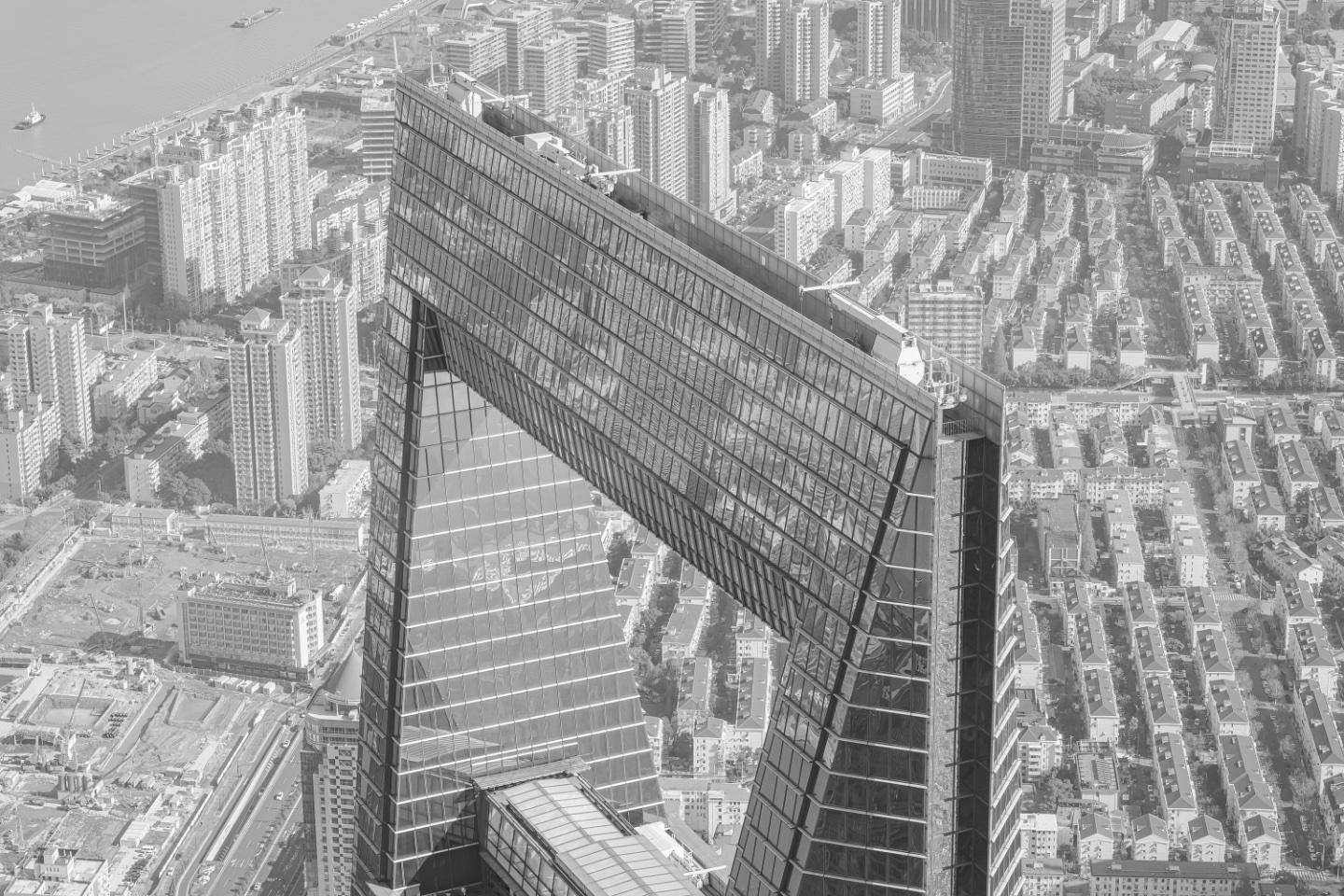

Shanghai Tower

2008 - 2015

632 m / 2,073 ft

583.4 m / 1,914 ft

3rd

In our latest trip, we visited the Shanghai Tower. It’s the third tallest building in the world and the tallest in China. After completion in 2016, it, alongside the Jin Mao and WFC, became the world’s only trio of supertalls.

The supertall trio · Leica CL ·

18mm · f/2.8 · 1/1250 · ISO 100

The supertall trio · Leica CL ·

18mm · f/2.8 · 1/1250 · ISO 100

Designated LEED Platinum, the building was constrained by a mix of environmental concerns and strict building codes. For example, the entirety of the building features two nested glass walls with an atrium in between. This design allows natural air convection, significantly reducing thermal stresses and energy use in the building. Architectural firm Gensler created a PDF about the facade design process that is a great read.

In the elevator to the top ·

Leica CL · 18mm · f/5.6 · 1/50 · ISO 1600

In the elevator to the top ·

Leica CL · 18mm · f/5.6 · 1/50 · ISO 1600

To me, the undulating surface has an organic sense of beauty, but is perhaps not as memorable as the other three buildings I have mentioned here. Regardless, the observation deck, with its 360-degree views is a must see. On a clear day, you can see how far the Shanghai megacity goes. You can also look down at the comparatively diminutive WFC and Jin Mao tower, which being the 12th and 34th tallest buildings in the world, would feel absolutely enormous anywhere else.

Two Shanghais

Looking out from top of the Shanghai Tower, I realized that my appreciation for skyscrapers has changed since that visit nearly two decades prior. I was initially fascinated by the amount of engineering that goes into extreme buildings. That fascination shifted as I started to see skyscrapers as cultural markers, and the results of complex systems of economics and politics.

Standing there on the 121st floor, looking down at the modernity of Pudong and the historical buildings in The Bund, a word came to mind — duality. The city, and the country as a whole, are defined by the coexistence of extremes.

Leica CL · 18mm · f/5.6 · 1/250 ·

ISO 100

Leica CL · 18mm · f/5.6 · 1/250 ·

ISO 100

In Shanghai, the Huangpu River divides old and new. In Puxi, you can find French Renaissance style buildings in the French Concession. Not too far away, you’ll find traditional Shikumen. In Pudong, you’ll find the aforementioned modern skyscrapers.

For breakfast, you can get a steamer full of Xiaolongbao on the cheap the way locals have for decades, but pay in an instant with the scan of a QR code.

Chinese life is as much defined by strict, top-down totalitarian control, as it is by the vibrant entrepreneurial Chinese spirit.

In Western media, China is often depicted as a monolith, yet being there on the streets, I knew it is nothing but. Standing in one of the world’s tallest structures, I could see a distinctly Chinese flavor of modernity. Yes, the skyscrapers were often designed and in-part constructed by foreigners. Yet, unlike the buildings of the Bund, they were heavily shaped by Chinese history and tastes.

The skyscrapers of Pudong are a must visit, not just for their remarkable scale, but because they are tangible manifestations of the duality of Shanghai.

Camera setup

Thanks to Q for reading drafts of this.