My obsession with industrial design

My love of industrial design started at an early age. That love turned into an obsession when I watched Objectified for the first time more than a decade ago.

Until then, I thought of designers as serious stark men donning all-black and working in all-white studios. Objectified [1] — specifically, the segment featuring Naoto Fukasawa — showed me how wrong I was. He spoke with childlike playfulness as he explained the thought process behind his iconic Muji CD player.

I started collecting some of his work, scouring online auction sites and second-hand stores in Japan, while sticking to the things that speak to me.

au Design project

Before the iPhone arrived in 2007 and completely upended the cellular phone stage, Japan had a vibrant, thriving culture of keitai denwa (携帯電話) or mobile phones. Mobile phone penetration in Japan eclipsed that of any other country. Technologies such as cameras, mobile games, video streaming, GPS navigation, and MP3 playback made it into Japanese phones years before anywhere else in the world.

Each season, Japan’s large mobile carriers released collections of phones, much like the fashion industry. Coming in various finishes and form factors, cell phones were not only indispensable tools but also symbols of style and culture.

In 2002, au [2], one of Japan’s largest cell phone carriers, embarked on a project to imagine mobile phones’ future. It solicited the help of numerous notable designers to create concepts just like automobile companies do. Some made it to series production, others stayed as concepts and can only be seen in exhibitions.

Birth of the INFOBAR

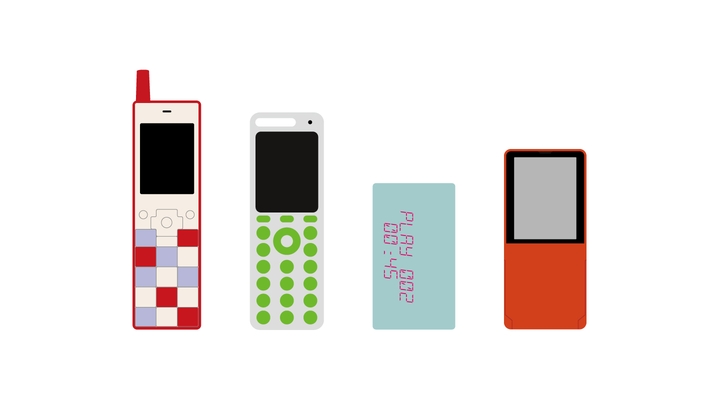

As part of the au Design project, au approached Naoto, head of IDEO Japan at the time, to help conceptualize a cell phone as a computer. 3G [3] was just being deployed across Japan, and PDAs (portable digital assistants) were very popular. Naoto envisioned a slab-like phone with candy-like keys and a monochrome screen on the front with a touch screen, including PDA-like functionality dominating the back.

After the director of the au Design project assessed demand for the INFOBAR, they decided to move forward with manufacturing. The eventual production INFOBAR lost the touch screen and gained a protruding antenna, but retained the candy-like slab aesthetic.

Of the many finishes available, the nishikigoi scheme inspired by koi fish scales became an icon. Over the next 15 years, INFOBAR has changed to fit the technology of the time, including becoming Android-powered. All along, the nishikigoi scheme has remained.

INFOBAR today

The iPhone and the ensuing proliferation of touchscreen smartphones have dramatically changed phone culture in Japan. There once were dozens of keitai available in every form factor and color imaginable. Now, most phones are variations on the slab-like touch screen phone pioneered by the iPhone.

Fortunately, there are still a few phones in the old style being developed and released. The INFOBAR is one of them. Just a few years ago, INFOBAR celebrated its 15th anniversary with the new INFOBAR XV, an exhibition in Tokyo [4], and a range of apparel and accessories [5].

Meeting Naoto

In 2015, I had the opportunity to attend a talk Naoto was giving in San Francisco. Before the talk, I walked up to him and pulled out an INFOBAR C02 cell phone he had designed from my jacket pocket. His face immediately lit up as he reached into his jacket pocket to reveal a newer INFOBAR A03. “I’ve got one too!” he said. I asked him to autograph the phone, and with a concerned look, he asked, “are you sure?” as if his signature would ruin the device.

I now display it in my studio as a prized possession and source of inspiration.

- Objectified · Gary Hustwit ↩︎

- au | carrier with the highest customer satisfaction rate in Japan ↩︎

- 3G · Wikipedia ↩︎

- au Design project公式デザインマガジン| INFOBARの最新情報はこちら ↩︎

- オリジナルグッズ INFOBAR COLLECTION 発売中♪| INFOBARの最新情報はこちら ↩︎

Thanks to Q for reading drafts of this. Video clip from Objectified. Some imagery is from au by KDDI.