Dieter Rams designed one of Gillette's most successful razors

9 min read Aug 12, 2019

Dieter Rams is best known for the products he created at Braun. Search his name on Google images, and you’ll see radios, lighters, clocks and record players. Many are in permanent collections of art galleries around the world and are considered design classics.

While these household objects are his most celebrated creations, he designed some quite ubiquitous products that he rarely gets credit for.

Wright

While watching the San Francisco screening of Gary Hustwit’s Rams, I noticed a razor laying on his desk.

As soon as I saw it, my mind filled with thoughts: “That razor must be something Dieter designed. It’s obvious he penned it!”, “I didn’t know he designed cheap things like razors.”, “I think my dad had one of those.”

When I went home from the screening, I found out it’s the Gillette Sensor from 1990. I started my research online and found surprisingly very little about its design and inception. There has been plenty written about the hundreds of millions of dollars Gillette spent developing and marketing it and the billions of dollars it made selling it. Surprisingly little-to-nothing has been written about who designed it.

What little I did find was a passing mention in a Wired article from 15 years ago.

Surprisingly, one of the shelves holds rows of Gillette safety razors and Oral-B toothbrushes. These familiar objects are among the least known but most ubiquitous of Rams’ designs – the razor was only recently discontinued, and the toothbrush was his best-selling product. They were both designed for Gillette shortly after the American giant acquired Braun in 1967.

[1]

The arrival of the Gillette Sensor

In 1967, Gillette, the American company that had cemented itself as an unrivaled purveyor of cheap, disposable razors and pens, acquired Braun, the smaller German manufacturer of home appliances. Over decades, Dieter Rams and the rest of the design team at Braun built its reputation for timelessly designed products.

Later, in the 70s, Gillette was the leader in the shaving space, specifically in market share of the then-growing, disposable razor segment. However, in the 80s, Gillette starting to see the warning signs of a looming slowdown. Sales of less-profitable disposable razors started displacing cartridge razors.

The trouble is that there is little profit in the quick-to-the-trash-can razors. They were expensive to make. Moreover, growth in unit sales of disposables has slowed in the last three years to 1 percent or 2 percent a year, and dollar sales have been flat, if not even declining slightly.

‘If the whole marketplace all of a sudden converted to disposable razors,’ said John W. Symons, the president of Gillette’s North Atlantic Shaving Group, ‘then you’d see a serious, serious decline in the shaving business.’

[2]

To combat the potential slowdown, it launched a ten-year effort and spent hundreds of millions of dollars to design its next shaver. The Sensor launched with plenty of fanfare. Gillette aired a Super Bowl advertisement and filled the pages of many magazines with advertisements.

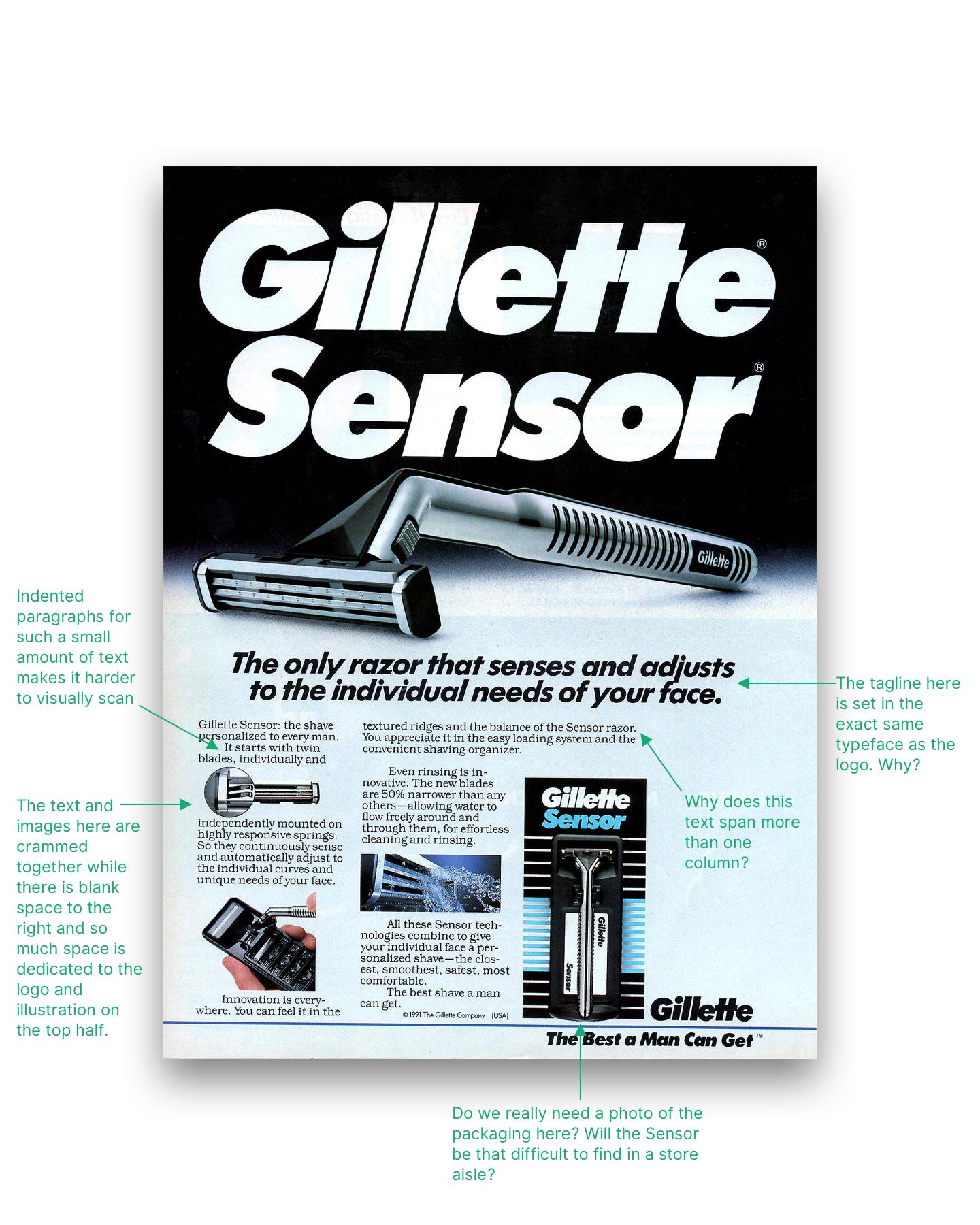

Even though Gillette spent hundreds of millions on the marketing, the execution wasn’t up-to-par with the quality of the industrial design of the Sensor. I’ve pointed out just a few of the multitude problems that exist with the magazine advertisement below.

The vast difference between the quality of the advertisement and the product it features is proof of how little Gillette’s leadership valued design. Unlike Braun before the acquisition, Gillette was a company concerned with profits first and foremost.

The Sensor in hand

Even though Gillette discontinued the original Sensor handle more than ten years ago, compatible Sensor cartridges and redesigned handles are still on sale.

I didn’t want a new handle, though. After some searching online, I found an original.

At first glance, it has the telltale signs of something penned by Dieter — something conforming to his Ten Principles for Good Design. The most apparent principle that it, like most of Dieter’s work, represents is the third.

Good design is aesthetic

The aesthetic quality of a product is integral to its usefulness because products we use every day affect our person and our well-being. But only well-executed objects can be beautiful.

The handle is a rounded cylinder with a series of semi-circular rubber grips along its length. They serve an essential purpose — making a wet handle easy to hold onto — but also contribute to its aesthetic balance.

The buttons used to disengage the cartridge are set apart from the handle with a black border. The ridged surface makes it instinctually obvious that they are meant to be pushed. They are an ideal example of principle number four.

Good design makes a product understandable

It clarifies the product’s structure. Better still, it can make the product talk. At best, it is self-explanatory.

The buttons are delightfully tactile and have the right amount of resistance. I couldn’t think of them working any other way. The mechanism they control is ingeniously designed. Two clips both hold the cartridge to the handle and allow it to rotate.

It may be made of injection-molded plastic and stamped metal. However, there is a feeling of heft and quality that would be expected from something handmade and expensive, not from an object that is mass-produced and affordable.

The Sensor would never be mistaken for something disposable. Simultaneously, it doesn’t scream out or draw any more attention than it deserves, conforming to principle five.

Good design is unobtrusive

Products fulfilling a purpose are like tools. They are neither decorative objects nor works of art. Their design should therefore be both neutral and restrained, to leave room for the user’s self-expression.

I tried using the Sensor with a new cartridge. While it didn’t provide as close of a shave as modern razors, it was nearly there. I suspect that an improved cartridge could provide a smoother shave.

The only unsightly characteristic is the prominent Gillette logo. That has a good explanation.

Dieter was famous for resisting higher-ups in Braun when they insisted that their products should have prominent logos on them. Dieter would instead include a small Braun logo on the back or in another unobtrusive manner such as aligning it with other visual elements.

The logo on this Braun RT 20 is aligned

with its controls · Photo Credit:

Wright

The logo on this Braun RT 20 is aligned

with its controls · Photo Credit:

Wright

The presence of such a large Gillette logo on the Sensor is a symptom of Dieter no longer having the final say in his designs.

“Rams and his five designers are getting more work from Gillette. Its new Sensor razor bears their imprint — though Rams hates the U. S. changes to his design, including a prominent nameplate.”

[3]

I can only imagine what Dieter’s first proposals looked like before being modified to include the logo.

Progress since the Sensor

Compared to what came before it, the Sensor is, according to Dieter’s principles, better designed.

It also successfully fought against the tide of completely disposable razors and became a commercial success. That success propelled Gillette to more profits and an even more commanding lead in the shaving market.

Fast forward two decades and Gillette is still a major contender. We have even more model lines and even more blades per cartridge. However, have we made progress?

Place it next to a modern Gillette Fusion razor, and it’s difficult to believe that they come from the same brand. Current Gillette products are made with thoughtless curves and arbitrary colors. They are in clear violation of Dieter’s tenth principle.

Good design is as little design as possible.

Less, but better – because it concentrates on the essential aspects, and the products are not burdened with non-essentials.

Back to purity, back to simplicity.

The Fusion is so ugly that I hide it in a cabinet. Why must a razor scream for so much attention? The Sensor, on the other hand, could be placed out on a bathroom countertop and quietly blend in when not in use.

The Sensor doesn’t seek more attention than it deserves · Photo Credit:

Michael DantLet’s say Gillette was to do some soul searching and go back to the magical design of the Sensor. I’d still have one significant doubt, namely, the blades.

The Sensor may be a beautiful, well-designed object. However, it is at its core built around a damaging model. The concept perhaps made perfect sense in the early 90s. Customers come for the well-made handle, and then the company has a recurring revenue stream because of disposable cartridges.

Today though, it’s clear that this model violates Dieter’s ninth principle.

Good design is environmentally-friendly

Design makes an important contribution to the preservation of the environment. It conserves resources and minimizes physical and visual pollution throughout the lifecycle of the product.

Each cartridge may be small, but at the scale at which Gillette produces them, the impact is immense. These cartridges find themselves in landfills, never biodegrading, and returning to the environment.

It’s a classic case of the tragedy of the commons. No one owns the environment, so no individual player is incentivized to devise a way to create razors with less environmental impact. Cartridges are affordable because of a mispriced externality, the environment, isn’t factored into the cost.

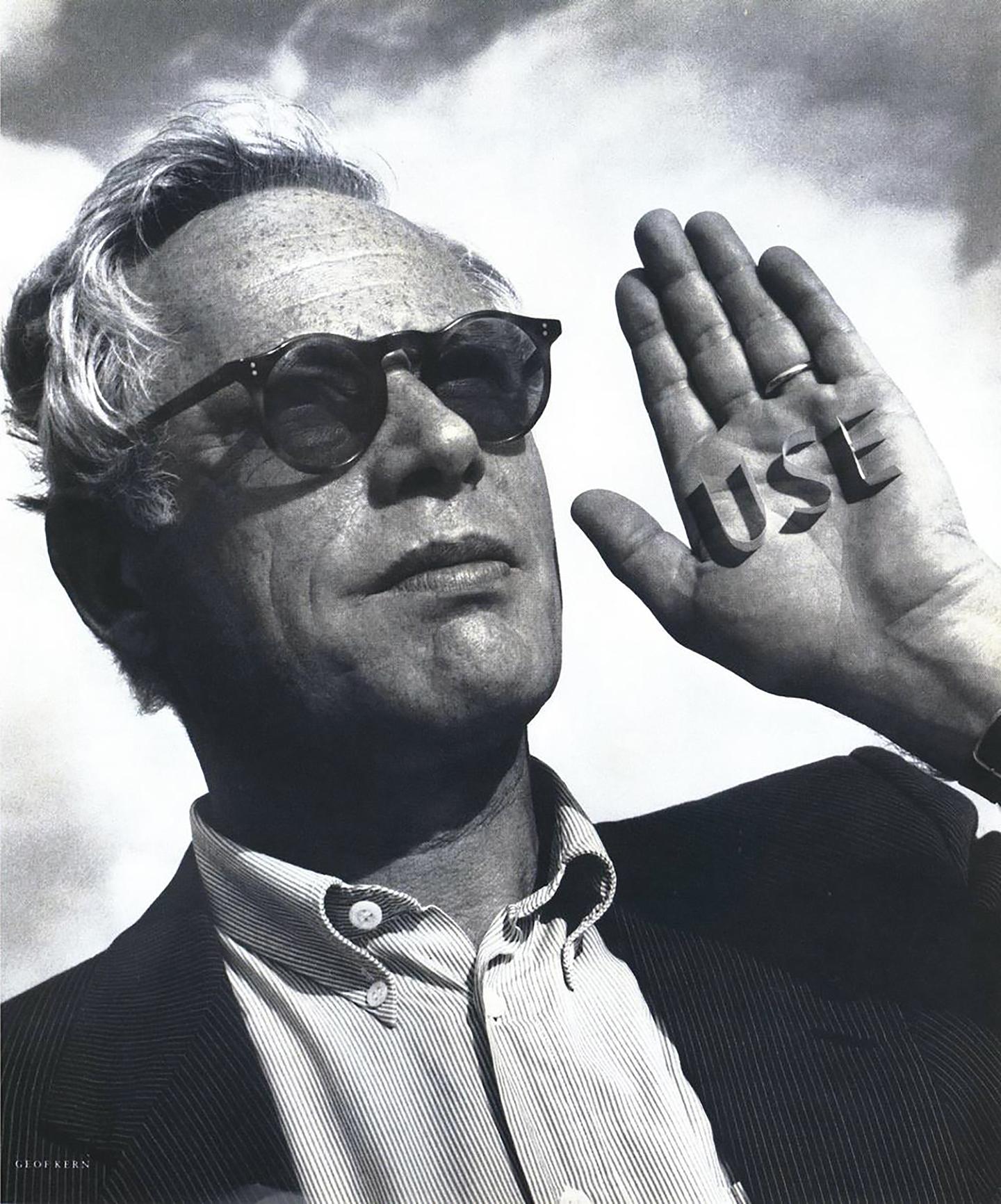

What would Dieter think today?

I wish I could ask Dieter what he thinks of the Gillette Sensor today. It’s one of his most ubiquitous designs. Yet, he is seldom credited for it. It was tremendously successful for Gillette, but it has also likely has had an equally tremendous impact on the environment.

In Rams, Dieter said that he is so concerned about the environmental impact of design that he wouldn’t even be a designer if he were to start again today.

Esquire

I wonder if he regrets creating disposable toothbrushes, pens, and razors at Gillette. Braun never explored the profitable model of disposables. Its products designed during Dieter’s tenure only require replacement parts when they malfunction.

Many of its products, like clocks, calculators, and juicers, have not been improved upon in the decades since their release. They don’t need improvement. They truly are timeless.

While the Sensor is beautifully designed, the waste it creates makes it and other razors like it, products that deserve reinvention.

The people of today understand environmental-impact. As Apple says on its minisite about the environment, “Truly innovative products leave their mark on the world instead of the planet.”

Respecting the environment is not just right; it can bolster a brand as it does for Apple. In the long term, this will lead to business success.

So, if Dieter were to design a new razor today, how would he go about it?

- Dieter Rams at home, 2004 · Wired ↩︎

- Gillette Challenge to the Disposables · The New York Times ↩︎

- The Brain Behind Braun · Innovation 1990: The Global Race · Business Week ↩︎

Thanks to Q for reading drafts of this.